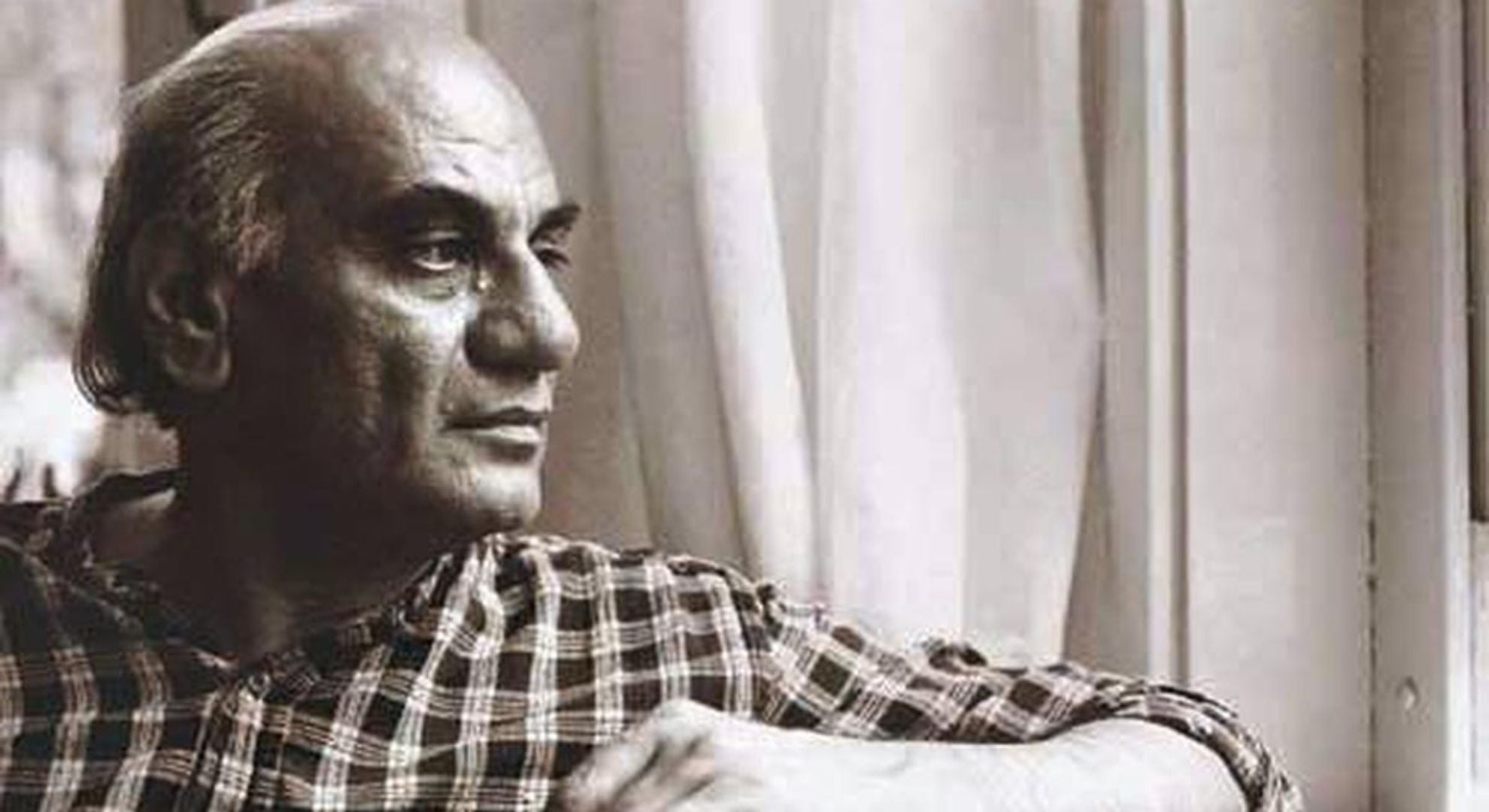

Alternate Takes : How Mani Kaul became a defining voice in India's Parallel Film Movement

In an industry where momentum often trumps meaning, Mani Kaul chose stillness. His frames lingered until silence became an event, and dialogue arrived not to explain but to hover, like a note in a raga suspended in air. This was cinema as contemplation, unbound by plot, spectacle, or speed.

Born in Jodhpur in 1944, Kaul entered the Film and Television Institute of India in the 1960s, when the country’s parallel cinema movement was gaining strength. Under Ritwik Ghatak’s mentorship, he learned that modern Indian cinema could draw from its own artistic traditions while engaging with the global avant-garde.

Kaul’s debut, Uski Roti (1969), announced his rejection of commercial cinema’s cause-and-effect logic. He treated time as elastic, letting emotion emerge through image and rhythm rather than narrative climax.

For Kaul, cinema was closer to music and painting than theatre. In Duvidha (1973), adapted from a Rajasthani folktale, still photographs, minimal movement, and voiceover evoked the intimacy of oral storytelling, as if the audience was entering a memory.

He was critical of Indian cinema’s disconnection from its visual heritage, arguing that too many filmmakers borrowed Western surface styles while ignoring India’s classical and folk traditions.

His documentaries, such as Dhrupad (1982), refused conventional explanations. The rhythm of the music dictated the rhythm of the film, making the act of listening its own experience.

As a teacher at FTII, Kaul urged students to question every shot and strip cinema to its essence. Many recall how easily he shifted from editing technique to the philosophy of perception. His influence can be seen in Indian independent filmmakers who treat cinema as a language in itself.

Though his work was acclaimed at international festivals and in academic circles, it rarely reached Indian theatres. In the algorithm-driven streaming era, its resistance to instant gratification feels even more radical. Watching a Mani Kaul film today is to enter a different rhythm of seeing and listening, one that reclaims slowness and reanchors art in its cultural soil.

Uski Roti (1969)

Mani Kaul’s debut feature, adapted from Mohan Rakesh’s story (who also wrote the dialogue), won the 1970 Filmfare Critics Award and is a landmark of the Indian New Wave. The film breaks from tradition by using minimal narrative, long static shots, and non-professional actors to focus on the emotional restraint and routine of a rural Punjabi woman, redefining cinematic time and attention.

Ashadh Ka Ek Din (1971)

Kaul's adaptation of Mohan Rakesh’s iconic play transforms theater into cinema by stripping the story to its performative and spatial essentials. The film features pre-recorded dialogue and painterly compositions influenced by Ajanta frescoes. The intellectual and emotional conflict between art and personal desire echoes in the minimal mise-en-scène, while the Himalayan setting and formalist dialogue delivery provide a timeless, introspective feel, integrating both psychological and historical layers.

Duvidha (1973)

An adaptation of Vijaydan Detha's Rajasthani folktale, Duvidha is an avant-garde meditation on female autonomy, identity, and the supernatural. Kaul eschews narrative convention, using saturated imagery, folk music, and sparse dialogue to evoke emotional and cultural ambiguity. The performances, deeply influenced by Bresson, emphasize gesture over psychology. The film's layered use of narration, visual metaphor, and mythic storytelling forms a complex feminist subtext within the feudal context of Rajasthan.

Puppeteers of Rajasthan (1974)

This documentary explores the disappearing tradition of Kathputli (puppetry) in Rajasthan. Kaul captures the daily lives, artistry, and performances of puppeteers, focusing on the oral and craft transmission of their art. Eschewing didactic narration, the film immerses the viewer in the rhythms of rural spectacle, documenting not just the art but the socio-economic challenges faced by these traditional performers. It stands as both ethnographic documentation and aesthetic observation.

A Historical Sketch of Indian Women (1975)

Through a formally restrained style, Kaul traces key shifts in the history of Indian women, examining how their roles are inscribed in classical texts, oral lore, and visual representation. The film foregrounds women's agency and marginalization, employing archival materials and voice-over narration to

Ghashiram Kotwal (1976)

A collaboration with a collective of FTII graduates, this experimental adaptation of Vijay Tendulkar's iconic play merges folk and classical performance elements with nonlinear cinematic technique. The film’s fragmented editing, ensemble staging, and use of Marathi Tamasha tradition create a stylized historical allegory about power, corruption, and resistance during the decline of the Maratha Empire, while also critiquing the politics of performance itself.

Chitrakathi (1977)

This documentary investigates the traditional narrative form of "Chitrakathi"—storytelling with illustrated panels in Maharashtra. Kaul’s camera lingers on storytellers' hands and faces, juxtaposing oral narration with visual imagery to explore memory, performativity, and the transmission of folk tradition threatened by modernity.

Arrival (1980)

A poetic documentary examining the sensory and emotional experience of arrival migrants, pilgrims and travelers. Kaul uses elliptical editing, soundscapes, and ephemeral visuals to meditate on displacement, anticipation, and the changing sense of place in modern India. The film refrains from voice-over, relying on immersive image-sound relationships.

Satah Se Uthata Admi (1980)

A landmark in Indian experimental cinema, this film adapts the poetry of Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh into a cinematic tapestry of images, memories, and shifting subjectivities. Avoiding linear plot, Kaul intercuts fiction and documentary, weaving together fragments of landscape, interior monologue, and surreal imagery to embody the fractured consciousness of the Indian intellectual in the era of political and social upheaval.

Dhrupad (1982)

A seminal exploration of North Indian classical music, this documentary is structured as both a meditation and performance film. Kaul foregrounds the rigor and spirituality of the dhrupad tradition, focusing on the Dagar Brothers. The camera captures sonic textures and the musicians' gestures, using rhythmically edited visuals to draw connections between music, time, and transcendence. The film has become a reference point in ethnomusicology and art cinema.

Mati Manas (1984)

Investigating the craft and cosmology of Indian potters, Kaul's documentary intertwines mythology, oral history, and the tactile process of pottery-making. Visual motifs of earth and handwork are interspersed with mythic voice-over, offering a meditation on continuity, labor, and artistic lineage. The film blurs boundaries between documentary and lyricism, characteristic of Kaul's late style.

Before My Eyes (1989)

This observational documentary explores themes of perception, memory, and mortality through sparse images, stillness, and voice-over. Kaul interacts intimately with people and spaces, focusing less on event than the act of seeing itself—each shot becoming a meditation on presence and temporality.

Siddheshwari (1989)

Blending documentary, fiction, and poetry, this film about singer Siddheshwari Devi is an avant-garde biography, fusing images of Banaras, music, myth, and fragments of memory. Kaul’s elliptical narrative resists chronology, instead mapping a spiritual and artistic journey that merges biography with broader themes of feminine creativity and oral tradition. This film won the National Award and is regarded as a masterwork of Indian nonfiction cinema.

Nazar (1991)

A distinctive adaptation of Dostoevsky’s short story "The Meek One," Kaul transposes the Russian original onto Mumbai, employing languid pacing, spectral camera work, and interior monologue. The narrative is fragmented and emotionally ambiguous, exploring psychological isolation and unstable perception within the city’s milieu. Visual sparseness and elliptical structure make it singular among Dostoevsky adaptations.

Idiot (1992)

Mani Kaul’s daring adaptation of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot transposes the narrative to contemporary Mumbai, where the epileptic Prince Myshkin (Ayub Khan-Din) is misjudged as ‘idiotic,’ alongside Shah Rukh Khan. Conceived as a four-part Doordarshan mini-series, it premiered at the New York Film Festival in 1992 but remained unreleased theatrically. Kaul embraces formal saturation, improvisation, “equipspatial” framing, and fractured temporality to echo Dostoevsky’s literary chaos, emerging as his most radical formalist work.

Naukar Ki Kameez (1999)

Based on Vinod Kumar Shukla's novella, the film examines class and existential ennui through the story of a clerk and his desire for a new shirt. Distilling narrative to its everyday elements, Kaul employs extended takes and deadpan performance to probe the smallness of personal aspiration amid social and bureaucratic inertia—highlighting the subtle violence of routine life and invisibility.

Mani Kaul on Patience and the Self in Cinema, Art and the Upanishads

Comments

MRS DEJANA IVICA — 1 day ago

TANGIBLE INFORMATION ABOUT LOAN PLANNING… THIS HAPPY NEW YEAR..

This is not a normal post that you see every day on the internet where people give fake reviews and false information about excellent financial assistance. I am aware that many of you have been scammed and that fake agents have taken advantage of those seeking loans. I will not call these normal reviews, I will call this situation where I live a witness to how you can get your loan when you meet the company’s requirements. It really does not matter if you have a good credit rating or government approval, all you need is a proper ID card and a valid IBAN number to be able to apply for a loan with an interest rate of 3%. The minimum amount is 1000 euros and the maximum amount that can be borrowed is 100,000,000 euros. I give you a 100% guarantee that you can get your loan through this reliable and honest company, we operate 24 hours online and provide loans to all citizens of Europe and outside Europe. They sent me a document that was checked and tested before I got the loan, so I invite anyone who needs a loan to visit them or contact them via email: michaelgardloanoffice@gmail.com

WhatsApp for Europe: +38591560870

WhatsApp for USA: +1 (717) 826-3251

After you contact them, let them know that Mrs. Dejana Ivica from Zagreb gave you the information. Seeing is believing and you will thank me later when you get a loan from them. I made a promise that after I get a loan from them, I will post the good news to everyone online. If you have friends or relatives, including colleagues, you can tell them about this offer and that it is happening.

sally — 9 days ago

Hello my name is Sally my fiancé broke up with me last week i was so sad I changed completely, I wasn’t eating and i wasn’t talking to anybody, I cried a lot, I was so depressed and stressed out that I was scared I’m going to end up in the hospital because of all the stress and depression until one day i search online on getting love tips because I Love & care about him deeply and I just want us to be together as a couple again and I want us to last forever then i found a powerful spell caster Called Priest Ade that he solved so many relationship problem then Priest Ade told me he will come back to me between 24hrs after he cast spell on him never believe it until my fiancé called me on the phone and told me he want us to come back and live happily together forever , Am so happy now that Priest Ade help me bring my finance back to me. Thanks so much Priest Ade he can also help you Email him at ancientspiritspellcast@gmail.com

Website ancientspellcast.wordpress.com WhatsApp: +2347070518515

Richard Liam — 12 days ago

I want to recommend you all to a lottery spell caster called Dr. Isa, who helped me win the sum of $3000,000 millions dollars. After I had spent more than $2000 on a ticket just because I believed that I was going to win, my dreams finally came through, all because of Dr Isa, the spell caster. If you have been searching for ways to win the lottery or any other game. Reach out to Dr Isa, who can help you. I found it so difficult until I met a kind man called Dr. Isa, who did everything perfectly for me. If you come across this review online, please get in touch with him for your lottery spell. His WhatsApp: +2347046030096 Or email: drisaspellcaster@gmail.com WEBSITE: https://drisaspellcaster.wixsite.com/dr-isa

Margaret Evelyn — 15 days ago

It is a very hard situation when playing the lottery and never won, or keep winning low fund not up to 100 bucks, i have been a victim of such a tough life, the biggest fund i have ever won was 100 bucks, and i have been playing lottery for almost 11 years now, things suddenly change the moment i came across a secret online, a testimony of a spell caster called Dr.Isa who help people win in any type of lottery numbers, i was not easily convinced, but i decided to give a try, now i am a proud to be a lottery winner with the help of Dr.Isa spell, i won 2,000,000 Million dollars and i am making this known to everyone out there who have been trying all day to win the lottery, believe me this is the only way to win the lottery, this is the real secret we all have been searching for.

His WhatsApp: +2347046030096

Email >> drisaspellcaster@gmail.com

Website: https://drisaspellcaster.wixsite.com/dr-isa

Christopher William —

DR UYI has done it for me, His predictions are 100% correct, He is real and can perform miracles with his spell. I am overwhelmed because I just won 336,000, 000 million Euro from a lottery jackpot game with the lottery number DR UYI gave me. I contacted DR UYI for help to win a lottery via Facebook Page DR UYI, he told me that a spell was required to be casted so that he can predict my winning, I provided his requirements for casting the spell and after casting the spell he gave the lottery numbers, I played and won 336,000,00 euros. How can I thank this man enough? His spell is real and like a God on Earth. Thank you for changing my life with your lottery winning numbers. Do you need help to win a lottery too? contact Dr UYI via drzukalottospelltemple@gmail.com OR WhatsApp on +17174154115

Richard Liam —

I want to recommend you all to a lottery spell caster called Dr. Isa, who helped me win the sum of $3000,000 millions dollars. After I had spent more than $2000 on a ticket just because I believed that I was going to win, my dreams finally came through, all because of Dr Isa, the spell caster. If you have been searching for ways to win the lottery or any other game. Reach out to Dr Isa, who can help you. I found it so difficult until I met a kind man called Dr. Isa, who did everything perfectly for me. If you come across this review online, please get in touch with him for your lottery spell. His WhatsApp: +2347046030096 Or email: drisaspellcaster@gmail.com WEBSITE: https://drisaspellcaster.wixsite.com/dr-isa

Richard Liam —

I want to recommend you all to a lottery spell caster called Dr. Isa, who helped me win the sum of $3000,000 millions dollars. After I had spent more than $2000 on a ticket just because I believed that I was going to win, my dreams finally came through, all because of Dr Isa, the spell caster. If you have been searching for ways to win the lottery or any other game. Reach out to Dr Isa, who can help you. I found it so difficult until I met a kind man called Dr. Isa, who did everything perfectly for me. If you come across this review online, please get in touch with him for your lottery spell. His WhatsApp: +2347046030096 Or email: drisaspellcaster@gmail.com WEBSITE: https://drisaspellcaster.wixsite.com/dr-isa

justinsimporios —

I was just a poor young man who didn’t find any luck after the first 2 years of playing the lottery. I tried everything humanly possible to hit the lottery, but, all my effort was nothing near positive. After the first two years of playing the lottery I got to understand that the lottery is deeper than Just regular numbers, believe me or not. Lottery is spiritual, money is power, every power has a controller, there are people who work in the supernatural.. My deeper quest to win the lottery exposed me to some very great people in the world. cheif frido is a man who say a word and the universe will honor him, I have seen several things like magic, but, chief frido is a god. with his help, after struggling for years I won $24M with the numbers chief frido gave me, after all the struggling and suffering, if you are very serious about winning the lottery contact chieffridospell@gmail.com +2347065417981