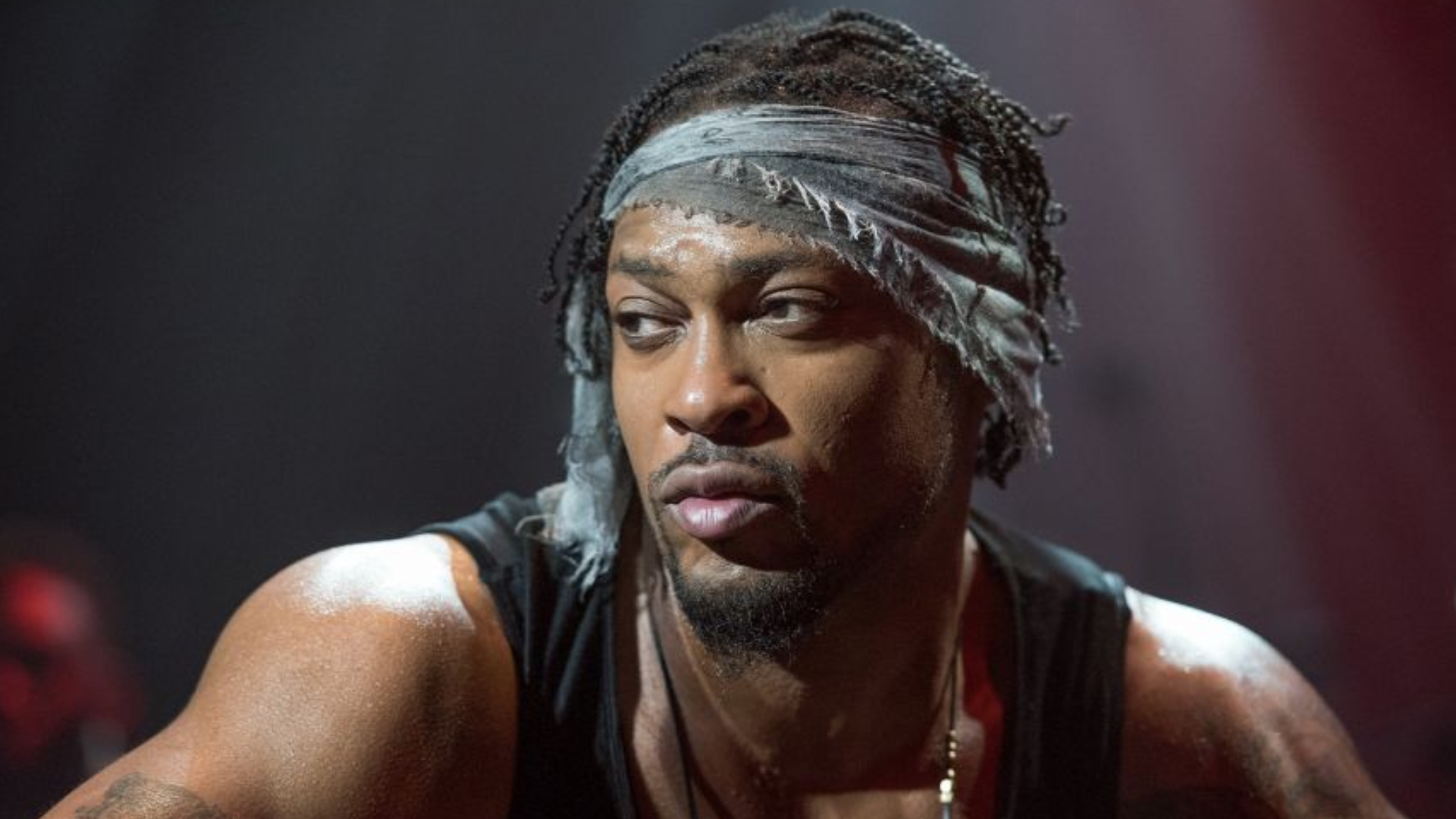

D' Angelo: 11 February 1974 - 14 October 2025

D’Angelo’s death sent a wave of grief through every corner of the music world — not just fans of Voodoo, but a generation of artists who had never known R&B without his influence.

Born Michael Eugene Archer in Richmond, Virginia, he grew up in church, playing piano by age three and absorbing the gospel rhythms that would anchor his sound. That belief — that music could move people like sermons — became his lifelong compass.

When Brown Sugar landed in 1995, R&B was glossy and mechanical. D’Angelo stripped it back. The record was warm and human, its grooves breathing between beats. He wrote, produced, and performed much of it himself, blending the sensuality of Marvin Gaye with hip-hop’s pulse. It sparked what would be labeled “neo-soul,” a term he dismissed, saying only, “I make Black music.”

With Voodoo in 2000, D’Angelo went further. Working with the Soulquarians — Questlove, J Dilla, Roy Hargrove, and others — he built something raw and unquantized. The grooves lagged and swayed, the songs stretched and breathed. It was revolutionary, and it won him Grammys — but the attention surrounding the “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” video made him a reluctant sex symbol, a role that pulled him away from the spotlight.

After years of silence, addiction, and retreat, he returned in 2014 with Black Messiah — part confession, part protest. Released amid unrest over police killings, the album’s tangled rhythms and dense harmonies spoke to faith, frustration, and resilience. “The one way I do speak out is through music,” he said.

Across just three albums, D’Angelo changed how modern soul feels. You can hear him in Frank Ocean’s stillness, SZA’s looseness, and Anderson .Paak’s swing. His belief in groove over perfection, patience over spectacle, remains the genre’s quiet law.

Now, as tributes fill timelines and playlists, the most fitting one is still the simplest: listen closely. Beneath every falsetto and every slow-burn bassline lives the pulse of an artist who made imperfection sound divine. D’Angelo’s gone, but the rhythm he taught music to trust still breathes in every beat.

18 Year Old D’Angelo singing “Tomorrow” in Church

Born Michael Eugene Archer in Richmond, Virginia, D’Angelo grew up in the pulpit’s shadow. His father was a Pentecostal minister, and by age three he was already playing piano during services. Sundays in church became his first classroom. Watching the choir move a congregation, he realized music could stir people’s spirits, a feeling that would define everything he later created.

D’Angelo speaks on his beginnings as a Pianist in his Father’s Church

Brown Sugar

Brown Sugar (1995)

This title track from his debut album opens D’Angelo’s story: a sultry fusion of ’70s soul warmth and hip-hop sensibility. With organ hooks, a minimalist groove and lyrics that double up the drug metaphor with romance, it set a template for neo-soul and made him a serious artist, not just a new voice.

Lady

1996

“Lady” became D’Angelo’s first major hit and his signature love song. Co-written with Raphael Saadiq, it blends smooth vocal layering, live bass, and the earthy warmth of vintage soul with the swing of hip-hop. The lyrics are simple but assured—a man completely captivated by his muse. “Lady” proved that D’Angelo could bridge underground soul musicianship with mainstream R&B success.

Cruisin’

1995

A cover of the Smokey Robinson classic, D’Angelo’s version adds string arrangements, flute and a modern groove, signalling his reverence for vintage soul while making it his own. The production shows his dual identity: steward of tradition and innovator.

Me and Those Dreamin’ Eyes of Mine

1996

A deeper cut from Brown Sugar, this introspective track shows D’Angelo’s songwriting maturing: gospel-tinged harmonies, funk backbone, vulnerability in the lyrics — wondering if his feelings keep him blind.

Devil’s Pie

2000

Pre-Voodoo single for the Belly soundtrack, “Devil’s Pie” is sharp: dark, funky, commenting on commercial excess with live drums and horns. It gave a clue that his next era would dig deeper — spiritually and musically.

Left & Right (feat. Redman & Method Man)

Voodoo (2000)

A bold lean into hip-hop-soul fusion: D’Angelo’s groove supports rappers and funk horn lines. It demonstrates the collaborative, experimental ethos of the Soulquarians era, showing that soul could be loose, messy, improvisatory.

Spanish Joint

Live at North Sea Jazz Festival 2015 (Released: 2000)

One of the more shimmering tracks on Voodoo, “Spanish Joint” moves with Afro-Latin flare: Latin guitar, dynamic horn arrangements (Roy Hargrove), shifting groove. It highlights D’Angelo pushing beyond standard soul into global soundscapes.

Untitled (How Does It Feel)

2000

The song and its video became iconic: a stripped-down plea for intimacy over a minimalist groove, and the visuals turned D’Angelo into a reluctant sex symbol. It remains one of modern R&B’s definitive moments.

Sugah Daddy

2014

The lead taste of Black Messiah, “Sugah Daddy” returned D’Angelo with swagger and analog warmth. It bridges funk rock, soul and swagger, hinting at the heavier themes he would embrace.

Really Love

2014

A slow-burn orchestral ballad from Black Messiah, “Really Love” balances delicate guitars, sweeping strings and his falsetto. It affirms his commitment to emotion and craft, framed for a modern era.

The Charade

2014

Arguably his most politically charged track, with punchy funk and lyrics about systemic injustice. “The Charade” places D’Angelo not just in the love-song lane but in the tradition of socially conscious soul.

1000 Deaths

2014

From Black Messiah, this track opens with a heavy beat, analog grit, and commentary on legacy and mortality. It underscores his depth beyond sex and sweetness to spiritual and existential terrain.

D’Angelo on Funk

From the 2012 interview with Nelson George for the documentary Finding The Funk.

Back to the Future (Part I & Part 2)

2014

These twin tracks from Black Messiah play like a suite; sprawling, exploratory, blending funk, rock, soul. They show D’Angelo’s ambition: not just hits, but albums as art.

Till It’s Done (Tutu)

2014

A tribute-inspired track (to Miles Davis’ Tutu), this song nods to jazz mastery while staying grounded in his groove universe. It shows how far his musical vision stretched.

Another Life

2014

The closing track on Black Messiah, it offers a bittersweet reflection: what comes after, what remains. It’s a fitting end to his album trilogy and a bridge to what might have been.

I Want You Forever

Jeymes Samuel x D’Angelo x JAY Z (2024)

Though not part of his main albums, this collaboration with Jay-Z and filmmaker Jeymes Samuel shows his final recorded statement. A nearly 10-minute funk-infused odyssey, it stands as a late note in his legacy, showing he was still evolving.

Comments

MRS DEJANA IVICA — 1 day ago

TANGIBLE INFORMATION ABOUT LOAN PLANNING… THIS HAPPY NEW YEAR..

This is not a normal post that you see every day on the internet where people give fake reviews and false information about excellent financial assistance. I am aware that many of you have been scammed and that fake agents have taken advantage of those seeking loans. I will not call these normal reviews, I will call this situation where I live a witness to how you can get your loan when you meet the company’s requirements. It really does not matter if you have a good credit rating or government approval, all you need is a proper ID card and a valid IBAN number to be able to apply for a loan with an interest rate of 3%. The minimum amount is 1000 euros and the maximum amount that can be borrowed is 100,000,000 euros. I give you a 100% guarantee that you can get your loan through this reliable and honest company, we operate 24 hours online and provide loans to all citizens of Europe and outside Europe. They sent me a document that was checked and tested before I got the loan, so I invite anyone who needs a loan to visit them or contact them via email: michaelgardloanoffice@gmail.com

WhatsApp for Europe: +38591560870

WhatsApp for USA: +1 (717) 826-3251

After you contact them, let them know that Mrs. Dejana Ivica from Zagreb gave you the information. Seeing is believing and you will thank me later when you get a loan from them. I made a promise that after I get a loan from them, I will post the good news to everyone online. If you have friends or relatives, including colleagues, you can tell them about this offer and that it is happening.

Christopher William —

DR UYI has done it for me, His predictions are 100% correct, He is real and can perform miracles with his spell. I am overwhelmed because I just won 336,000, 000 million Euro from a lottery jackpot game with the lottery number DR UYI gave me. I contacted DR UYI for help to win a lottery via Facebook Page DR UYI, he told me that a spell was required to be casted so that he can predict my winning, I provided his requirements for casting the spell and after casting the spell he gave the lottery numbers, I played and won 336,000,00 euros. How can I thank this man enough? His spell is real and like a God on Earth. Thank you for changing my life with your lottery winning numbers. Do you need help to win a lottery too? contact Dr UYI via drzukalottospelltemple@gmail.com OR WhatsApp on +17174154115

Big Bull —

SELLING FULLZ SSN USA NIN UK SIN CANADA

AUS SPAIN ITALY GERMANY Fullz available

Fresh Stuff & Fresh Spammed

Available in bulk quantity

Valid & guaranteed info

DL front back with selfie

DL with issue & exp dates

DL with SSN

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS—> USA

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS—> UK

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN—> CANADA

Tax Return Filling Fullz & KYC Stuff

HACKING & SPAMMING TOOLS & TUTORIALS

COMPLETE PACKAGES WITH ALL TOOLS & TUTORIALS INCLUDED

SCAM PAGES|SCRIPTING

CASH OUT & CARDING STUFF

LOAN METHODS & CARDING METHODS

Many Other stuff for cashing out|filling for loans|KYC

All stuff will be 101% Genuine, nothing generated or edited

Contact us here only (Be aware from scammers)

Telegram – @ killhacks ’ @ leadsupplier

What’s App – +1 7277..88..612..9

TG Channel – t.me/ leadsproviderworldwide

Email – hacksp007 at gmail dot com

VK Messenger – @ leadsupplier

USA STUFF:

SSN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS EMPLOYMENT & BANK INFO FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS DL ISSUE & EXP INFO FULLZ

FULLZ WITH MVR

USA DL|ID FRONT BACK WITH SELFIE & SSN

USA LLC DOCS

USA W-2 FORMS

USA Passport Photos

High Credit Scores Pros

SweepStakes & Dead Fullz

Business EIN Company Pros|EIN Lookup

Dumps & CC with CVV

-———————————————————————-

UK (UNITED KINGDOM) STUFF:

NIN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS FULLZ

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS SORT CODE & ACCOUNT NUMBER FULLZ

High Credit Scores Pros Fullz

UK DL Front Back with Selfie

UK Email & Phone number Leads

UK Passports

Consumer Leads UK

Bank Leads with sort code & account number UK Fullz

-———————————————————————-

CA (CANADA) STUFF:

SIN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN FULLZ

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN PHONE POST CODE FULLZ

Canada DL Front Back with Selfie

CA Email & Phone Number leads

High Credit Score Fullz

Canada Passports

-————————————————————————

OTHER STUFF WE’RE PROVIDING WITH GUARANTEE:

EMAIL LEADS (Crypto|Unemployment|Casino|Medical|Health|Office365)

Car Database with Vehicle registration numbers

Email Combos

I.P & Proxies

Different type of Docs available

TOOLS AVAILABLE

SMTP RDP SHELLS C-PANELS

KALI LINUX

RATS & VIRUSES

Web-Mailers

SMS & Email Senders

Scam Pages & Scripting

Office365 Spamming Stuff

#FULLZ #TOOLS #TUTORIALS #EBOOKS #USAFULLZ #UKFULLZ #CAFULLZ #DLPHOTOS

#HACKING #SPAMMING #CARDING #SPOOFING #LEADSUSA #COMBOS #CRYPTOLEADS

#UKLEAD #CANADALEADS #HIGHCREDITSCOREPROS #CRYPTOPAYMENTS #PROS #OFFICE365

#SENDERS #FULLZSHOP #DUMPSCVV #CCFULLZ #USACC #FULLZDUMPS #DUMPSID #DUMPSDL

#EMAILLEADS

Contact here only (Be aware from scammers)

Telegram – @ killhacks ’ @ leadsupplier

What’s App – +1 7277..88..612..9

TG Channel – t.me/ leadsproviderworldwide

Email – hacksp007 at gmail dot com

VK Messenger – @ leadsupplier

rocio cardenar —

Investment scams are becoming increasingly common in the world of cryptocurrency, with many individuals falling victim to fraudulent schemes promising high returns on their investments. These scams can result in the loss of significant amounts of money, leaving victims feeling helpless and devastated.

CoinsRecoveryWorldwide is a trusted and reliable resource for individuals who have fallen victim to investment scams involving Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. They specialize in helping clients recover their lost assets and funds through their expertise and experience in navigating the complex world of cryptocurrency scams.

CoinsRecoveryWorldwide works tirelessly to investigate and track down the perpetrators of these scams, working with law enforcement agencies and other authorities to ensure that justice is served. They provide a range of services to assist clients in recovering their assets, including legal representation, forensic analysis, and negotiation with scammers.

If you have been the victim of an investment scam involving Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies, don’t hesitate to reach out to CoinsRecoveryWorldwide for assistance. They have a proven track record of success in recovering lost assets for their clients and can help you navigate the process of recovering your funds. Don’t let scammers get away with your hard-earned money – contact CoinsRecoveryWorldwide today for help in recovering your assets.

Contact information

WEBSITE; https://coinsrecoveryworldwide.mobirisesite.com/ EMAIL.COINSRECOVERYWORLDWIDE@GMAIL.COM WHATSAPP:+17658236083]

MRS DEJANA IVICA —

TANGIBLE INFORMATION ABOUT CHRISTMAS LOAN FOR PLANNING…

This is not a normal post that you see every day on the internet where people make false statements and false information about huge financial assistance.. I am aware that many of you have been scammed and that fake agents have taken advantage of those seeking loans. I will not call this a normal statement, I will call this situation where I live a witness to how you can get your loan when you meet the company’s requirements. It really does not matter to have a good credit rating or government approval, all you need is a valid ID card and a valid IBAN number to be able to apply for a loan with an interest rate of 3%. The minimum amount is 1000 euros and the maximum amount that can be borrowed is 100,000,000 euros. I give you a 100% guarantee that you can get your loan through this reliable and honest company, we operate 24 hours online and provide loans to all citizens of Europe and outside Europe. They sent me a document that was checked and tested as valid before I got the loan, so I invite anyone who needs a loan to visit them or contact them via

Email: michaelgardloanoffice@gmail.com

WhatsApp for Europe: +385915608706

WhatsApp for USA: +1 (717) 826-3251

After you contact them, let them know that Ms. Dejana Ivica from Zagreb gave you the information. Seeing is believing and you will thank me later when you get a loan from them. I made a promise that after I get a loan from them, I will post the good news to everyone online. If you have friends or relatives, including colleagues, you can tell them about this offer and that it is happening this CHRISTMAS.

Fat Rosa —

HOW I RECOVERED MY LOST CRYPTO FROM FAKE BROKER ONLINE.

I had lost over $752,000 by someone I met online on a fake investment project. After the loss, I had a long research on how to recover the lost funds. I came across a lot of Testimonies about THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS. I contacted them providing the necessary information and it took the experts about 48 hours to locate and help recover my stolen money. If anyone is looking for a Recovery firm to Recover your lost Crypto. You can contact THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS . I hope this helps as many out there who are victims and have lost to these fake online investment scammers. You can contact them by using

Email at support@thehackangels.com

Website at www.thehackangels.com

WhatsApp +1(520)200-2320

Fat Rosa —

HOW I RECOVERED MY LOST CRYPTO FROM FAKE BROKER ONLINE.

I had lost over $752,000 by someone I met online on a fake investment project. After the loss, I had a long research on how to recover the lost funds. I came across a lot of Testimonies about THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS. I contacted them providing the necessary information and it took the experts about 48 hours to locate and help recover my stolen money. If anyone is looking for a Recovery firm to Recover your lost Crypto. You can contact THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS . I hope this helps as many out there who are victims and have lost to these fake online investment scammers. You can contact them by using

Email at support@thehackangels.com

Website at www.thehackangels.com

WhatsApp +1(520)200-2320

Big Bull —

USA UK CANADA FULLZ AVAILABLE

FRESH DATABASES & VALID INFO

Guaranteed stuff with replacement offer

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS USA

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN CA

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS SORT-CODE UK

REAL DL & ID Front Back with Selfie

Children Fullz 2011-2023

Young Age & Old Age Fullz

CC Fullz with CVV & Billing Address

Dumps with Pin Track 101 & 202

Contact for any query & order here:

TG – @ leadsupplier / @ killhacks

What’s App – (+1).. (727). (788). (6129).

TG Channel – t.me/leadsproviderworldwide

VK Messenger ID – @ leadsupplier

E-mail – bigbull0334 at gmail dot com

*(Be aware from scammers using our cloned names on TG)

Providing fresh stuff with 100% guarantee

80% to 90% connectivity ratio

All stuff will be fresh & genuine

USA FULL NAME SSN DOB DL ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL ACCOUNT & ROUTING NUMBER

UK FULL NAME NIN DOB DL ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL SORT CODE & ACCOUNT NUMBER

CANADA FULL NAME SIN DOB ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL MMN

#SSN #SSNDOBDL #SellSSN #CCShop #CCSELLCVV #ShopSSNDOBDLADDRESS #FULLZ #SSNFULLZ

#REALDLSCAN #YoungAgeFullz #Fullzseller #USAFULLZ #FULLZUSA #SellerSSNDOB #ShopSSNDOB

#SIN #SINDOBDL #SellSIN #SINMMNFULLZ #MMNPROSSIN #MMNSIN #CCShop #CCSELLCVV #ShopSINDOBDLADDRESS #FULLZ #SINFULLZ

#REALDLSCAN #YoungAgeFullz #Fullzseller #CANADAFULLZ #FULLZCANADA

#NIN #NINDOBDL #SellNIN #CCShop #CCSELLCVV #ShopNINDOBDLADDRESS #FULLZ #NINFULLZ

#REALDLSCAN #YoungAgeFullz #Fullzseller #UKFULLZ

Other stuff we’re providing as well, listed below:

===========

DL Front back with selfie USA|UK|CA|AUS|GR|FR|RU|CHINA e.t.c

Fullz with MVR & W-2 Form

Business Pros Company fullz with EIN

High credit scores pros (700+ score)

Dead fullz bulk quantity

Tax return filling fullz (FASFA|UBER|DOORDASH|SBA|PUA|UI|BENEFITS)

USA Fullz with DL Front Back with SSN & Selfie

Email Leads available in different categories:

===========

Crypto Leads

Fresh Sweep Stakes

Business P2P leads

Medical Leads

Education Leads

Country wise Leads

Bank Details Leads with phone numbers

Specific States & Cities Leads USA UK CAN

Car Database leads with registration No.

Doctor’s Leads

Health Leads

Facebook|Amazon|LinkedIn|Ebay Leads

Payday Leads

Mortgage Leads

All type of Sp’a’mming Tools & Tutorials are available for learning purpose.

>SMTP

>RDP

>BRUTES

>SHELLS

>C-panels

>Web-Mailers

>Bulk SMS & E-Mail Senders

>Sc@mpages & Scripting

>Cash out & Carding Tutorials

>H@cking Tools & Tutorials

Many other Stuff we can provide on demand as well

Feel free to contact with us, we’ll assist you 24/7

We’re providing stuff for learning to make money as well

Proper guidance & assistance will be provided

Waiting for you guy’s

Here we are for you:

-TG – @ leadsupplier / @ killhacks

-What’s App – (+1).. (727). (788). (6129).

-TG Channel – t.me/leadsproviderworldwide

-VK Messenger ID – @ leadsupplier