Jazz Diplomacy: How Music Became America's Unlikely Cold War Weapon

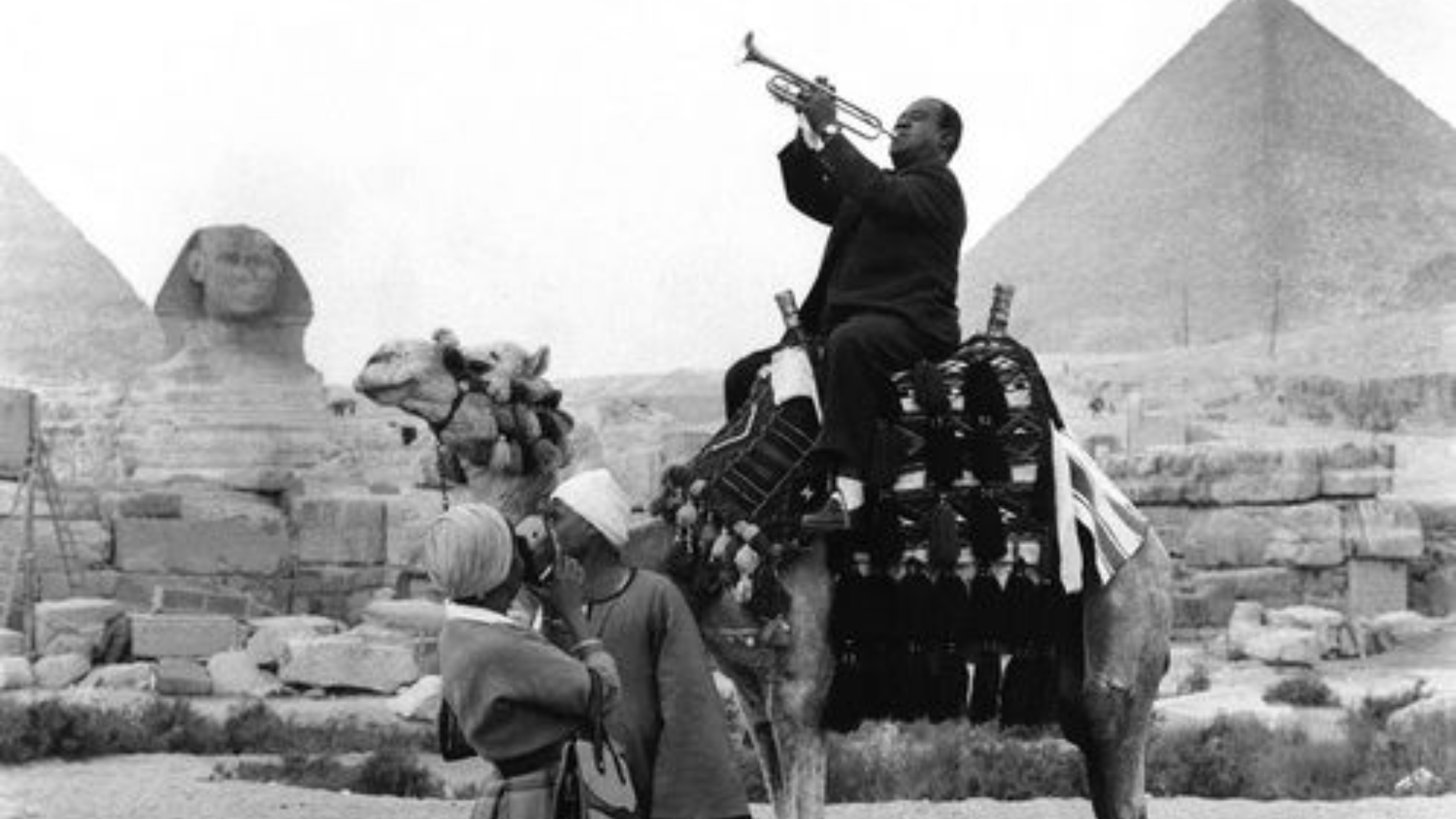

In 1956, with the Cold War intensifying and global opinion shifting, the U.S. State Department made an unusual bet: that a trumpet might travel farther than a tank. Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck, Duke Ellington - artists who had redefined American music were recruited to serve as cultural diplomats. Their assignment was ambitious and contradictory: to represent American freedom to the world, even as their own freedoms were limited at home.

This initiative, known as the Jazz Ambassadors program, was an effort to win hearts and minds through soft power. In the eyes of Washington, jazz was the ideal propaganda tool; vibrant, improvisational, distinctly American. It symbolized individual liberty, collaboration, and innovation. But the men sent abroad were the same musicians who were often refused entry into hotels, and barred from stages in their own country.

The program was launched during the Eisenhower administration and intensified under Kennedy. As Soviet rhetoric painted America as a racist, imperialist state, the U.S. needed a counter-narrative. Musicians were sent on tours that spanned the Middle East, Africa, Eastern Europe, and South Asia. They performed in concert halls and dusty open-air arenas, held jam sessions, and broke language barriers more effectively than any ambassador could.

Yet the contradictions followed. Armstrong famously cancelled a government-sponsored trip to the USSR in 1957 after the violent response to school desegregation in Arkansas. Dave Brubeck refused to perform without his Black bassist, Eugene Wright, even when it meant cancelling part of his tour.

In sending these artists abroad, the U.S. was promoting a version of itself that didn’t exist back home. If jazz represented freedom, it wasn’t because the government said so. It was because it had been created by people who had none, and who found a way to speak anyway.

In a world again shaped by ideological divisions, perhaps there’s something to learn from a strategy that trusted culture over coercion. The Jazz Ambassadors didn’t end wars. But they changed minds, cracked doors, and left behind echoes that still ask: What does freedom really sound like?

In 1956, the United States decided that Jazz – improvised, collaborative, and unmistakably American could travel farther than tanks, projecting freedom across borders at the height of the Cold War.

The State Department launched the Jazz Ambassadors program, sending musicians like Armstrong, Gillespie, and Ellington to represent America. They weren’t diplomats by training, but they carried a language of freedom that no government official could match.

The State Department launched the Jazz Ambassadors program, sending musicians like Armstrong, Gillespie, and Ellington to represent America. They weren’t diplomats by training, but they carried a language of freedom that no government official could match.

Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a Harlem power broker, was instrumental in convincing Washington that jazz was the perfect tool to counter Soviet propaganda about American racism and repression.

Powell believed music could tell a story that politics could not. By lobbying Eisenhower’s administration, he set in motion one of the most unusual Cold War strategies sending musicians into contested regions as frontline ambassadors of liberty.

Dizzy Gillespie, with his trademark bent trumpet and unstoppable charisma, led the very first Jazz Ambassadors tour in 1956 with a racially integrated band and Quincy Jones as music director.

His band toured Southern Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia. Wherever they went, they drew massive crowds sometimes skeptical, often chaotic, but more often leaving audiences exhilarated. Jazz was improvisation, and so was diplomacy.

The first official concert of the Jazz Ambassadors took place in Abadan, Iran setting a precedent for using music as a direct form of American outreach.

In dusty arenas and grand theaters, the musicians broke barriers that politicians never could. Their sound carried an immediacy – joy, defiance, freedom – that crossed language and cultural divides with extraordinary effectiveness.

In Athens, skepticism turned into chaos and then into celebration, as audiences lifted Dizzy into the streets, proof of the power of music to shift moods in real time.

The concert started tensely but ended in euphoria. This became a recurring theme: audiences doubted at first, then surrendered to the energy of jazz, finding in its improvisation a glimpse of something liberating.

The concert started tensely but ended in euphoria. This became a recurring theme: audiences doubted at first, then surrendered to the energy of jazz, finding in its improvisation a glimpse of something liberating.

U.S. diplomats wrote home that a single jazz concert could achieve more goodwill in an evening than years of speeches, treaties, or even military shows of strength.

They marveled at the reach: teenagers humming riffs, parents bringing families to concerts, newspapers covering encores. Music carried sincerity—its persuasive power was subtle, emotional, and in many ways unstoppable.

At the same time, millions behind the Iron Curtain were tuning into Willis Conover’s nightly jazz broadcast on Voice of America, a radio show more influential than many political speeches.

Conover’s baritone voice introduced Ellington, Armstrong, and Brubeck to listeners from Prague to Moscow. For audiences starved of free expression, jazz became a lifeline an audible reminder of the freedoms they lacked.

Yet the contradictions were glaring. The very musicians sent abroad to embody freedom often returned to segregation, bans, and daily racism in their own country.

Audiences abroad noticed too. The power of jazz was undeniable, but it exposed America’s hypocrisy: how could the nation sell liberty overseas while denying it at home? Musicians lived this paradox onstage and off.

Audiences abroad noticed too. The power of jazz was undeniable, but it exposed America’s hypocrisy: how could the nation sell liberty overseas while denying it at home? Musicians lived this paradox onstage and off.

Dave Brubeck refused to perform without his Black bassist, Eugene Wright, even when venues and governments demanded otherwise. His quartet’s integrity became a diplomatic statement in itself.

Brubeck canceled shows rather than compromise. On foreign tours, the sight of an integrated band carried as much symbolic weight as the music itself. It said: this is what freedom should look like.

Brubeck and his wife Iola later created The Real Ambassadors, a satirical jazz musical with Armstrong that confronted America’s hypocrisy head-on.

Performed at Monterey in 1962, it mocked Cold War propaganda while elevating musicians as the true ambassadors. It remains one of the boldest cultural commentaries to come out of the program.

Performed at Monterey in 1962, it mocked Cold War propaganda while elevating musicians as the true ambassadors. It remains one of the boldest cultural commentaries to come out of the program.

Dizzy’s tours left behind records like World Statesman and Dizzy in South America, capturing the energy of the Jazz Ambassadors abroad.

These albums were more than souvenirs they were artifacts of diplomacy. The covers themselves sometimes declared their mission: jazz as the voice of America to the wider world.

These albums were more than souvenirs they were artifacts of diplomacy. The covers themselves sometimes declared their mission: jazz as the voice of America to the wider world.

In 1963, Duke Ellington undertook a massive State Department tour through the Middle East, South Asia, and beyond, absorbing sounds that would transform his music.

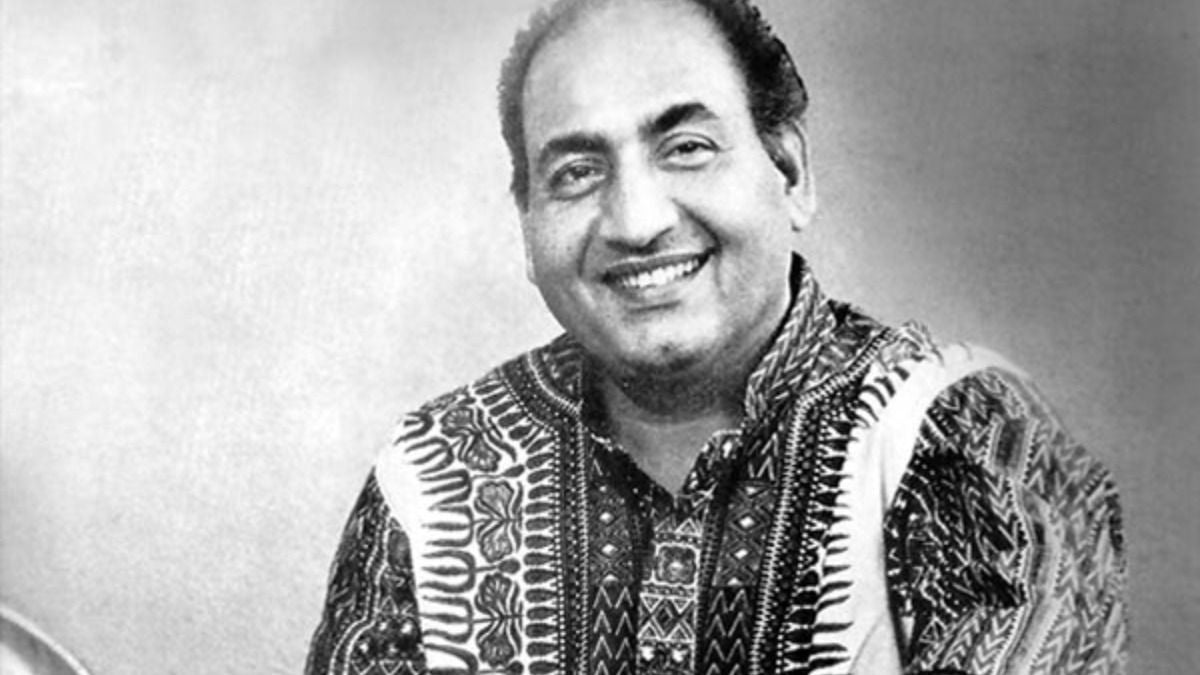

Ellington played to audiences in India, Pakistan, Lebanon, Jordan, and more. Each stop was both concert and conversation, with Duke taking in regional melodies and rhythms that would later reshape his compositions.

Ellington played to audiences in India, Pakistan, Lebanon, Jordan, and more. Each stop was both concert and conversation, with Duke taking in regional melodies and rhythms that would later reshape his compositions.

In 1963, Duke Ellington undertook a massive State Department tour through the Middle East, South Asia, and beyond, absorbing sounds that would transform his music.

Ellington played to audiences in India, Pakistan, Lebanon, Jordan, and more. Each stop was both concert and conversation, with Duke taking in regional melodies and rhythms that would later reshape his compositions.

Ellington played to audiences in India, Pakistan, Lebanon, Jordan, and more. Each stop was both concert and conversation, with Duke taking in regional melodies and rhythms that would later reshape his compositions.

Comments

MRS DEJANA IVICA — 1 day ago

TANGIBLE INFORMATION ABOUT LOAN PLANNING… THIS HAPPY NEW YEAR..

This is not a normal post that you see every day on the internet where people give fake reviews and false information about excellent financial assistance. I am aware that many of you have been scammed and that fake agents have taken advantage of those seeking loans. I will not call these normal reviews, I will call this situation where I live a witness to how you can get your loan when you meet the company’s requirements. It really does not matter if you have a good credit rating or government approval, all you need is a proper ID card and a valid IBAN number to be able to apply for a loan with an interest rate of 3%. The minimum amount is 1000 euros and the maximum amount that can be borrowed is 100,000,000 euros. I give you a 100% guarantee that you can get your loan through this reliable and honest company, we operate 24 hours online and provide loans to all citizens of Europe and outside Europe. They sent me a document that was checked and tested before I got the loan, so I invite anyone who needs a loan to visit them or contact them via email: michaelgardloanoffice@gmail.com

WhatsApp for Europe: +38591560870

WhatsApp for USA: +1 (717) 826-3251

After you contact them, let them know that Mrs. Dejana Ivica from Zagreb gave you the information. Seeing is believing and you will thank me later when you get a loan from them. I made a promise that after I get a loan from them, I will post the good news to everyone online. If you have friends or relatives, including colleagues, you can tell them about this offer and that it is happening.

Big Bull —

SELLING FULLZ SSN USA NIN UK SIN CANADA

AUS SPAIN ITALY GERMANY Fullz available

Fresh Stuff & Fresh Spammed

Available in bulk quantity

Valid & guaranteed info

DL front back with selfie

DL with issue & exp dates

DL with SSN

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS—> USA

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS—> UK

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN—> CANADA

Tax Return Filling Fullz & KYC Stuff

HACKING & SPAMMING TOOLS & TUTORIALS

COMPLETE PACKAGES WITH ALL TOOLS & TUTORIALS INCLUDED

SCAM PAGES|SCRIPTING

CASH OUT & CARDING STUFF

LOAN METHODS & CARDING METHODS

Many Other stuff for cashing out|filling for loans|KYC

All stuff will be 101% Genuine, nothing generated or edited

Contact us here only (Be aware from scammers)

Telegram – @ killhacks ’ @ leadsupplier

What’s App – +1 7277..88..612..9

TG Channel – t.me/ leadsproviderworldwide

Email – hacksp007 at gmail dot com

VK Messenger – @ leadsupplier

USA STUFF:

SSN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS EMPLOYMENT & BANK INFO FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS DL ISSUE & EXP INFO FULLZ

FULLZ WITH MVR

USA DL|ID FRONT BACK WITH SELFIE & SSN

USA LLC DOCS

USA W-2 FORMS

USA Passport Photos

High Credit Scores Pros

SweepStakes & Dead Fullz

Business EIN Company Pros|EIN Lookup

Dumps & CC with CVV

-———————————————————————-

UK (UNITED KINGDOM) STUFF:

NIN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS FULLZ

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS SORT CODE & ACCOUNT NUMBER FULLZ

High Credit Scores Pros Fullz

UK DL Front Back with Selfie

UK Email & Phone number Leads

UK Passports

Consumer Leads UK

Bank Leads with sort code & account number UK Fullz

-———————————————————————-

CA (CANADA) STUFF:

SIN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN FULLZ

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN PHONE POST CODE FULLZ

Canada DL Front Back with Selfie

CA Email & Phone Number leads

High Credit Score Fullz

Canada Passports

-————————————————————————

OTHER STUFF WE’RE PROVIDING WITH GUARANTEE:

EMAIL LEADS (Crypto|Unemployment|Casino|Medical|Health|Office365)

Car Database with Vehicle registration numbers

Email Combos

I.P & Proxies

Different type of Docs available

TOOLS AVAILABLE

SMTP RDP SHELLS C-PANELS

KALI LINUX

RATS & VIRUSES

Web-Mailers

SMS & Email Senders

Scam Pages & Scripting

Office365 Spamming Stuff

#FULLZ #TOOLS #TUTORIALS #EBOOKS #USAFULLZ #UKFULLZ #CAFULLZ #DLPHOTOS

#HACKING #SPAMMING #CARDING #SPOOFING #LEADSUSA #COMBOS #CRYPTOLEADS

#UKLEAD #CANADALEADS #HIGHCREDITSCOREPROS #CRYPTOPAYMENTS #PROS #OFFICE365

#SENDERS #FULLZSHOP #DUMPSCVV #CCFULLZ #USACC #FULLZDUMPS #DUMPSID #DUMPSDL

#EMAILLEADS

Contact here only (Be aware from scammers)

Telegram – @ killhacks ’ @ leadsupplier

What’s App – +1 7277..88..612..9

TG Channel – t.me/ leadsproviderworldwide

Email – hacksp007 at gmail dot com

VK Messenger – @ leadsupplier

Johnson Elizabeth —

Best Crypto Recovery Company – visit Optimistic Hacker Gaius.

Optimistic Hacker Gaius is the best crypto recovery company. I was scammed and lost a significant amount of funds, but after reading a review about their success in recovering lost crypto, I reached out. Within just 6 hours, they traced and recovered most of my lost assets! Their service was fast, professional, and exceeded my expectations. I’m extremely grateful for their help and highly recommend them to anyone facing similar issues. Thank you, Optimistic Hacker Gaius!

Contact them at the following.

Visit Their Website: optimistichackargaius. c o m

Email: support@ optimistichackargaius. c o m

Text them on WhatsApp: (+44 737 674 0569).

MRS DEJANA IVICA —

TANGIBLE INFORMATION ABOUT CHRISTMAS LOAN FOR PLANNING…

This is not a normal post that you see every day on the internet where people make false statements and false information about huge financial assistance.. I am aware that many of you have been scammed and that fake agents have taken advantage of those seeking loans. I will not call this a normal statement, I will call this situation where I live a witness to how you can get your loan when you meet the company’s requirements. It really does not matter to have a good credit rating or government approval, all you need is a valid ID card and a valid IBAN number to be able to apply for a loan with an interest rate of 3%. The minimum amount is 1000 euros and the maximum amount that can be borrowed is 100,000,000 euros. I give you a 100% guarantee that you can get your loan through this reliable and honest company, we operate 24 hours online and provide loans to all citizens of Europe and outside Europe. They sent me a document that was checked and tested as valid before I got the loan, so I invite anyone who needs a loan to visit them or contact them via

Email: michaelgardloanoffice@gmail.com

WhatsApp for Europe: +385915608706

WhatsApp for USA: +1 (717) 826-3251

After you contact them, let them know that Ms. Dejana Ivica from Zagreb gave you the information. Seeing is believing and you will thank me later when you get a loan from them. I made a promise that after I get a loan from them, I will post the good news to everyone online. If you have friends or relatives, including colleagues, you can tell them about this offer and that it is happening this CHRISTMAS.

emily faye —

I have been suffering from Herpes for the past 1 years and 8 months, and ever since then I have been taking series of treatment but there was no improvement until I came across testimonies of Dr. Silver on how he has been curing different people from different diseases all over the world, then I contacted him as well. After our conversation he sent me the medicine which I took according to his instructions. When I was done taking the herbal medicine I went for a medical checkup and to my greatest surprise I was cured from Herpes. My heart is so filled with joy. If you are suffering from Herpes or any other disease you can contact Dr. Silver today on this Email address: drsilverhealingtemple@gmail.com

Fat Rosa —

HOW I RECOVERED MY LOST CRYPTO FROM FAKE BROKER ONLINE.

I had lost over $752,000 by someone I met online on a fake investment project. After the loss, I had a long research on how to recover the lost funds. I came across a lot of Testimonies about THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS. I contacted them providing the necessary information and it took the experts about 48 hours to locate and help recover my stolen money. If anyone is looking for a Recovery firm to Recover your lost Crypto. You can contact THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS . I hope this helps as many out there who are victims and have lost to these fake online investment scammers. You can contact them by using

Email at support@thehackangels.com

Website at www.thehackangels.com

WhatsApp +1(520)200-2320

Fat Rosa —

HOW I RECOVERED MY LOST CRYPTO FROM FAKE BROKER ONLINE.

I had lost over $752,000 by someone I met online on a fake investment project. After the loss, I had a long research on how to recover the lost funds. I came across a lot of Testimonies about THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS. I contacted them providing the necessary information and it took the experts about 48 hours to locate and help recover my stolen money. If anyone is looking for a Recovery firm to Recover your lost Crypto. You can contact THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS . I hope this helps as many out there who are victims and have lost to these fake online investment scammers. You can contact them by using

Email at support@thehackangels.com

Website at www.thehackangels.com

WhatsApp +1(520)200-2320

Usman Bello —

ALPHA KEY BTC RECOVERY: SEEK ADVICE FROM A LICENSED CRYPTO RECOVERY HACKER

Only a small number of skilled hackers has the special hacking knowledge and abilities needed to recover lost Bitcoin. Although there are a lot of recovery websites available, it’s crucial to exercise caution because 99% of them are run by con artists who pose as trustworthy businesses. It is preferable to go for a reliable hacker who can assist you in getting your money back, such as Alpha Key BTC Recovery. I lost $326k in Bitcoin due to mining, but they were able to retrieve it. contact info below

Mail : Alphakey@consultant.com

Website : www.alphakeyrecovery.com

WhatsApp contact :15714122170

Signal contact:15403249396