Street Poet: How Chamkila Defied Punjabi Norms Through his Music

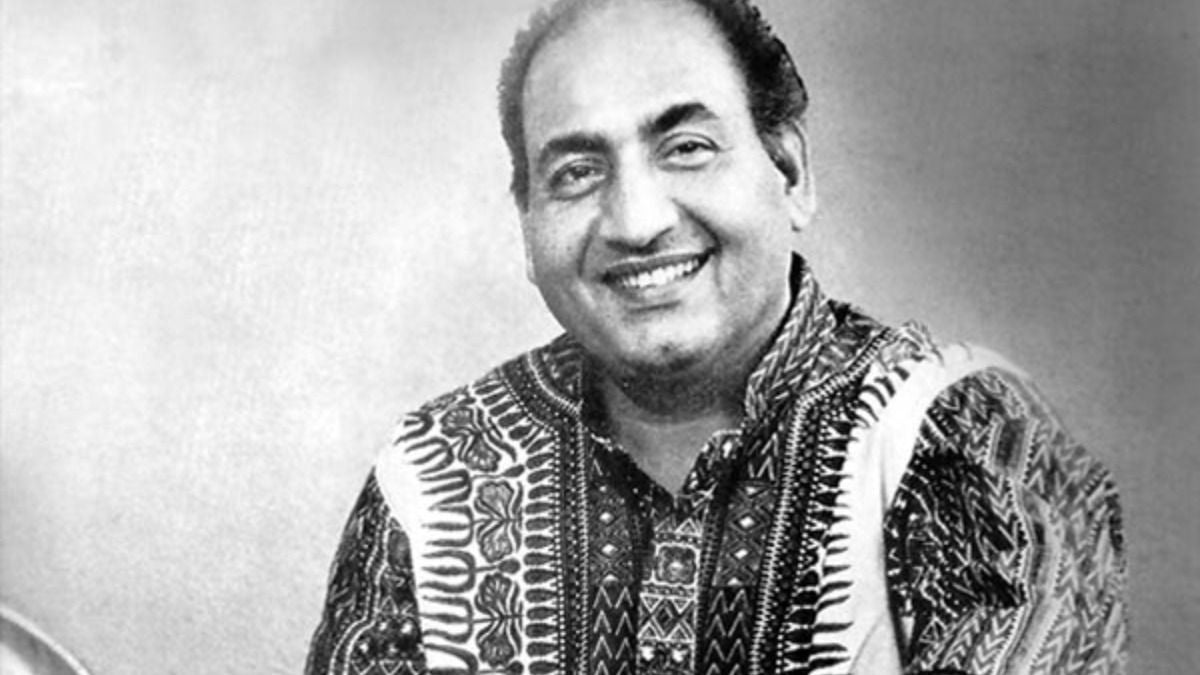

Amar Singh Chamkila remains one of Indian music’s most paradoxical figures. A man from the margins who sang in the idiom of the streets, his voice travelled far beyond its origins - echoing through fields, truck radios, wedding processions, and drawing rooms alike.

He confronted Punjab’s unspoken truths; and provoked moralists even as he united communities in song, mirroring the desires, frustrations, and contradictions of ordinary Punjabis.

Chamkila’s early life was shaped by loss and labor. After his mother’s death, he worked odd jobs, joined a cloth mill, and trained as an electrician to support his family. Music, however, was both refuge and rebellion. He picked up the harmonium, tumbi, and dholki, performing with village drama troupes and learning how rhythm and story could bind a crowd.

The arrival of the cassette player in the 80s transformed Punjab’s musical landscape; suddenly, songs could travel faster than radio or television ever allowed. Chamkila’s raw, melodic voice became the soundtrack of the villages and small towns that had emerged from the Green Revolution.

Chamkila began writing, composing, and performing songs about infidelity, alcohol, and female desire - subjects that society shunned but everyone recognized. His lyrics, full of colloquial words like chapkar, patola, and peengh, blurred the line between the sacred and profane. In his world, the vaili—the local gangster—was a folk hero, a symbol of defiance against authority and class hierarchy.

But fame in Punjab came with peril. On March 8, 1988, in Mehsampur, gunmen opened fire as Chamkila arrived for a performance, killing him, his wife Amarjot, and two band members. He was twenty-eight. The case remains unsolved.

Decades later, the same themes of caste pride, feudal masculinity, and rural bravado run through the songs of newer icons like Sidhu Moose Wala. To listen to Chamkila today is to hear a Punjab both exuberant and uneasy—where art speaks what society won’t, and where one man’s forbidden voice still echoes across a landscape that never quite let him live, but refuses to let him die.

Jija Lak Minle

Jija Lak Minle LP; 1980

This song is one of Chamkila’s early hits, from the LP Jija Lak Minle. It captures youthful longing, village romance, and his signature direct style. With simple instrumentation and emotional delivery, it resonated powerfully in rural Punjab. The song helped solidify his reputation as a folk-pop voice speaking to everyday life among rural audiences.

Hikk Utte So Ja Ve

Hikk Utte So Ja Ve LP; 1985

This title track from his 1985 LP Hikk Utte So Ja Ve showcases Chamkila’s emotional depth. The song’s theme is introspective, invoking solitude, loss, or longing. Its simple arrangement allows his voice and lyrics to dominate, creating an intimate space for listeners to reflect. The record further extended his reach beyond live shows into home listening audiences.

Lak Mera Kach Warga

Lak Mera Kach Warga LP; 1982

“Lak Mera Kach Warga” uses metaphor to speak of fragility, identity, and social belonging. Chamkila blends folk melodies with bold, earthy lyrics about life’s uncertainties. It remains a favorite in retrospective collections of his work.

Naam Jap Le

Naam Jap Le; 1986

A more spiritual or exhortative turn in Chamkila's output is “Naam Jap Le.” Released circa 1986, it appeals to devotional sensibilities, urging remembrance. This shows Chamkila's range — not limited to earthy or provocative themes but also able to touch on religious devotion in his own voice.

Baba Tera Nankana

“Baba Tera Nankana” is among his devotional or lyrical songs invoking Sikh heritage (Nankana Sahib). Though precise release date or LP attribution is unclear, the song is a part of his charitable/spiritual side, reflecting a more contemplative mood. It remains part of Chamkila’s long-term legacy through compilations.

Tar Gayi Ravidas Di Pathri

Another song with devotional or socially rooted tone, “Tar Gayi Ravidas Di Pathri” references the saint Ravidas, connecting regional, religious, and communal sentiment. While footnotes on its original album or year are sparse, it shows Chamkila’s engagement with folk beliefs and spiritual culture.

Sharbat Wango

“Sharbat Wango” evokes imagery of sweetness, longing, and refreshment — a metaphorical emotional balm. The melody, likely folk-oriented, gives Chamkila space to bring raw vocal nuance, while the lyric invites listeners to feel solace or comfort.

Talwar Main Kalgidhar Di

A devotional/historical register: the title invokes the Guru (“Kalgidhar”). These religious albums broadened his reach and helped him pivot away from “obscenity” accusations into sangat spaces. Year/title presence is corroborated in the Wikipedia bio’s discography summary.

Chak Lao Drivero Purje Nu

A workaday vignette (“driver, take up the parts”), this one spotlights his fascination with trades, travel, and the road. It’s chatty, kinetic, and tailor-made for live repartee. Appears on the Lak Mera Kach Warga LP.

Pehle Lalkare Naal

Jija Lak Minle; 1980

A breakout duet with Amarjot from Chamkila’s early LP era. Built on punchy folk phrasing and conversational lyric, it spotlights his gift for everyday idiom and call-and-response energy that played brilliantly on stage. Often cited among his earliest “hits,” it sits on the 1980 HMV LP alongside other staples from this phase.

Takue Te Takua

Lak Mera Kach Varga; 1982

Frequently mentioned as his first recorded song in biographies, it also appears on the Lak Mera Kach Varga tracklist. The lyric’s wordplay and percussion-forward bounce foreshadow his later stage ferocity.

Banhan Wich Bhabi

The title points to family dynamics (sister/sister-in-law), a theme Chamkila mined for humour and friction. It’s typical of his domestic micro-dramas — short scenes set to nimble folk rhythm.

Mirza

Mirza appears in Chamkila’s performance/folk song compilations, but there’s no verifiable album or year attribution in credible discographic sources. The versions online show his characteristic vocal intensity and rural storytelling motifs. In many uploads, Mirza is grouped with hits such as Pehle Lalkare Naal, implying it is part of his core repertoire.

Imtiaz Ali’s Amar Singh Chamkila (2024) revisits the life of Punjab’s most controversial musician

Starring Diljit Dosanjh and Parineeti Chopra, the film traces Chamkila’s meteoric rise, his provocative lyrics, and his violent death in 1988. Shot like a musical documentary and scored by A.R. Rahman, it captures both the euphoria and tragedy of an artist who gave voice to the unspeakable.

Comments

MRS DEJANA IVICA — 1 day ago

TANGIBLE INFORMATION ABOUT LOAN PLANNING… THIS HAPPY NEW YEAR..

This is not a normal post that you see every day on the internet where people give fake reviews and false information about excellent financial assistance. I am aware that many of you have been scammed and that fake agents have taken advantage of those seeking loans. I will not call these normal reviews, I will call this situation where I live a witness to how you can get your loan when you meet the company’s requirements. It really does not matter if you have a good credit rating or government approval, all you need is a proper ID card and a valid IBAN number to be able to apply for a loan with an interest rate of 3%. The minimum amount is 1000 euros and the maximum amount that can be borrowed is 100,000,000 euros. I give you a 100% guarantee that you can get your loan through this reliable and honest company, we operate 24 hours online and provide loans to all citizens of Europe and outside Europe. They sent me a document that was checked and tested before I got the loan, so I invite anyone who needs a loan to visit them or contact them via email: michaelgardloanoffice@gmail.com

WhatsApp for Europe: +38591560870

WhatsApp for USA: +1 (717) 826-3251

After you contact them, let them know that Mrs. Dejana Ivica from Zagreb gave you the information. Seeing is believing and you will thank me later when you get a loan from them. I made a promise that after I get a loan from them, I will post the good news to everyone online. If you have friends or relatives, including colleagues, you can tell them about this offer and that it is happening.

Christopher William —

DR UYI has done it for me, His predictions are 100% correct, He is real and can perform miracles with his spell. I am overwhelmed because I just won 336,000, 000 million Euro from a lottery jackpot game with the lottery number DR UYI gave me. I contacted DR UYI for help to win a lottery via Facebook Page DR UYI, he told me that a spell was required to be casted so that he can predict my winning, I provided his requirements for casting the spell and after casting the spell he gave the lottery numbers, I played and won 336,000,00 euros. How can I thank this man enough? His spell is real and like a God on Earth. Thank you for changing my life with your lottery winning numbers. Do you need help to win a lottery too? contact Dr UYI via drzukalottospelltemple@gmail.com OR WhatsApp on +17174154115

Big Bull —

SELLING FULLZ SSN USA NIN UK SIN CANADA

AUS SPAIN ITALY GERMANY Fullz available

Fresh Stuff & Fresh Spammed

Available in bulk quantity

Valid & guaranteed info

DL front back with selfie

DL with issue & exp dates

DL with SSN

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS—> USA

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS—> UK

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN—> CANADA

Tax Return Filling Fullz & KYC Stuff

HACKING & SPAMMING TOOLS & TUTORIALS

COMPLETE PACKAGES WITH ALL TOOLS & TUTORIALS INCLUDED

SCAM PAGES|SCRIPTING

CASH OUT & CARDING STUFF

LOAN METHODS & CARDING METHODS

Many Other stuff for cashing out|filling for loans|KYC

All stuff will be 101% Genuine, nothing generated or edited

Contact us here only (Be aware from scammers)

Telegram – @ killhacks ’ @ leadsupplier

What’s App – +1 7277..88..612..9

TG Channel – t.me/ leadsproviderworldwide

Email – hacksp007 at gmail dot com

VK Messenger – @ leadsupplier

USA STUFF:

SSN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS EMPLOYMENT & BANK INFO FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS DL ISSUE & EXP INFO FULLZ

FULLZ WITH MVR

USA DL|ID FRONT BACK WITH SELFIE & SSN

USA LLC DOCS

USA W-2 FORMS

USA Passport Photos

High Credit Scores Pros

SweepStakes & Dead Fullz

Business EIN Company Pros|EIN Lookup

Dumps & CC with CVV

-———————————————————————-

UK (UNITED KINGDOM) STUFF:

NIN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS FULLZ

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS SORT CODE & ACCOUNT NUMBER FULLZ

High Credit Scores Pros Fullz

UK DL Front Back with Selfie

UK Email & Phone number Leads

UK Passports

Consumer Leads UK

Bank Leads with sort code & account number UK Fullz

-———————————————————————-

CA (CANADA) STUFF:

SIN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN FULLZ

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN PHONE POST CODE FULLZ

Canada DL Front Back with Selfie

CA Email & Phone Number leads

High Credit Score Fullz

Canada Passports

-————————————————————————

OTHER STUFF WE’RE PROVIDING WITH GUARANTEE:

EMAIL LEADS (Crypto|Unemployment|Casino|Medical|Health|Office365)

Car Database with Vehicle registration numbers

Email Combos

I.P & Proxies

Different type of Docs available

TOOLS AVAILABLE

SMTP RDP SHELLS C-PANELS

KALI LINUX

RATS & VIRUSES

Web-Mailers

SMS & Email Senders

Scam Pages & Scripting

Office365 Spamming Stuff

#FULLZ #TOOLS #TUTORIALS #EBOOKS #USAFULLZ #UKFULLZ #CAFULLZ #DLPHOTOS

#HACKING #SPAMMING #CARDING #SPOOFING #LEADSUSA #COMBOS #CRYPTOLEADS

#UKLEAD #CANADALEADS #HIGHCREDITSCOREPROS #CRYPTOPAYMENTS #PROS #OFFICE365

#SENDERS #FULLZSHOP #DUMPSCVV #CCFULLZ #USACC #FULLZDUMPS #DUMPSID #DUMPSDL

#EMAILLEADS

Contact here only (Be aware from scammers)

Telegram – @ killhacks ’ @ leadsupplier

What’s App – +1 7277..88..612..9

TG Channel – t.me/ leadsproviderworldwide

Email – hacksp007 at gmail dot com

VK Messenger – @ leadsupplier

MRS DEJANA IVICA —

TANGIBLE INFORMATION ABOUT CHRISTMAS LOAN FOR PLANNING…

This is not a normal post that you see every day on the internet where people make false statements and false information about huge financial assistance.. I am aware that many of you have been scammed and that fake agents have taken advantage of those seeking loans. I will not call this a normal statement, I will call this situation where I live a witness to how you can get your loan when you meet the company’s requirements. It really does not matter to have a good credit rating or government approval, all you need is a valid ID card and a valid IBAN number to be able to apply for a loan with an interest rate of 3%. The minimum amount is 1000 euros and the maximum amount that can be borrowed is 100,000,000 euros. I give you a 100% guarantee that you can get your loan through this reliable and honest company, we operate 24 hours online and provide loans to all citizens of Europe and outside Europe. They sent me a document that was checked and tested as valid before I got the loan, so I invite anyone who needs a loan to visit them or contact them via

Email: michaelgardloanoffice@gmail.com

WhatsApp for Europe: +385915608706

WhatsApp for USA: +1 (717) 826-3251

After you contact them, let them know that Ms. Dejana Ivica from Zagreb gave you the information. Seeing is believing and you will thank me later when you get a loan from them. I made a promise that after I get a loan from them, I will post the good news to everyone online. If you have friends or relatives, including colleagues, you can tell them about this offer and that it is happening this CHRISTMAS.

Fat Rosa —

HOW I RECOVERED MY LOST CRYPTO FROM FAKE BROKER ONLINE.

I had lost over $752,000 by someone I met online on a fake investment project. After the loss, I had a long research on how to recover the lost funds. I came across a lot of Testimonies about THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS. I contacted them providing the necessary information and it took the experts about 48 hours to locate and help recover my stolen money. If anyone is looking for a Recovery firm to Recover your lost Crypto. You can contact THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS . I hope this helps as many out there who are victims and have lost to these fake online investment scammers. You can contact them by using

Email at support@thehackangels.com

Website at www.thehackangels.com

WhatsApp +1(520)200-2320

Usman Bello —

ALPHA KEY BTC RECOVERY: SEEK ADVICE FROM A LICENSED CRYPTO RECOVERY HACKER

Only a small number of skilled hackers has the special hacking knowledge and abilities needed to recover lost Bitcoin. Although there are a lot of recovery websites available, it’s crucial to exercise caution because 99% of them are run by con artists who pose as trustworthy businesses. It is preferable to go for a reliable hacker who can assist you in getting your money back, such as Alpha Key BTC Recovery. I lost $326k in Bitcoin due to mining, but they were able to retrieve it. contact info below

Mail : Alphakey@consultant.com

Website : www.alphakeyrecovery.com

WhatsApp contact :15714122170

Signal contact:15403249396

lucas e,merson —

After over 30 years in the cockpit as a commercial pilot, flying across continents and safely landing thousands of passengers, I was ready for retirement. Like many others, I had put part of my earnings into cryptocurrency—Bitcoin, specifically—as a long-term investment. Over time, that small investment grew substantially, eventually reaching £2,000,000. It wasn’t just a number on a screen; it was my safety net, my future, my reward for decades of hard work and sacrifice. Then, in a single moment, it was all gone. I logged into my crypto wallet one morning and was met with an empty balance—zero. My entire portfolio had vanished. What I later learned was that I had been the victim of a sophisticated form of cyber theft known as cryptojacking. The hackers had exploited vulnerabilities in my system, compromised my private keys, and stealthily transferred every last coin to their own wallets. The feeling? Crippling. I reached out to every avenue I could think of—banks, law enforcement, online crypto forums—but the answer was always the same: “There’s nothing we can do.” I was devastated. It felt like years of planning and saving had been erased overnight. That was until I came across.COINSRECOVERYWORLDWIDE Naturally, I was cautious. The internet is riddled with “recovery experts” who prey on victims twice. But from my first contact with Coinsrecoveryworldwide, the difference was obvious. Their team was transparent, knowledgeable, and deeply empathetic. They didn’t offer empty guarantees—they offered action, and more importantly, they delivered. Here’s what set them apart: Unmatched Technical Expertise Coinsrecoveryworldwide began by conducting an advanced forensic analysis of my case. They traced my stolen Bitcoin through multiple layers of obfuscation—including mixers, tumblers, and shadow wallets commonly used by criminals to launder crypto assets. Their team used blockchain analytics and cyber-intelligence tools to follow the trail where others had hit a dead end. Dark Web Surveillance and Server Penetration They didn’t stop at blockchain tracking. Using legal and ethical cyber-infiltration methods, they breached one of the attacker’s remote servers—uncovering a treasure trove of data: stolen credentials, transaction logs, and access routes. This breakthrough allowed them to identify the specific IPs and even the hardware fingerprints used during the theft. Collaboration with Exchanges and Global Partners Coinsrecoveryworldwide then leveraged their global network and worked directly with several crypto exchanges to flag, freeze, and intercept the stolen assets before they could be laundered or converted. They also collaborated with cybersecurity partners to neutralize parts of the botnet infrastructure the hackers had used. Successful Recovery Within weeks, 95% of my stolen funds—equivalent to £1,900,000—was securely returned to a new, uncompromised wallet. Watching that balance reappear felt like being rescued from a plane crash. I was overwhelmed with relief and gratitude. This experience has taught me that all is not lost after a scam—not when you have the right people in your corner. Coinsrecoveryworldwide didn’t just recover my funds. They restored my sense of justice, safety, and peace. They are not just another tech firm—they are specialists in real-world cybercrime intervention. They combine unmatched technical acumen with genuine care for the people they help. To anyone facing the same nightmare I went through: don’t give up. Coinsrecoveryworldwide is the real deal. If they could recover my £2,000,000 there’s hope for you too. Contact COINSRECOVERYWORLDWIDE Security Company 📧

🌐 Website: [https://coinsrecoveryworldwide.mobirisesite.com/] 📧 Email: Coinsrecoveryworldwide@gmail.com 💬 WhatsApp:+1765-823-6083

Take the step to secure your future—you’re not alone

GH —

USA UK CANADA FULLZ AVAILABLE

FRESH DATABASES & VALID INFO

Guaranteed stuff with replacement offer

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS USA

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN CA

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS SORT-CODE UK

REAL DL & ID Front Back with Selfie

Children Fullz 2011-2023

Young Age & Old Age Fullz

CC Fullz with CVV & Billing Address

Dumps with Pin Track 101 & 202

Contact for any query & order here:

TG – @ leadsupplier / @ killhacks

What’s App – (+1).. (727). (788). (6129).

TG Channel – t.me/leadsproviderworldwide

VK Messenger ID – @ leadsupplier

E-mail – bigbull0334 at gmail dot com

*(Be aware from scammers using our cloned names on TG)

Providing fresh stuff with 100% guarantee

80% to 90% connectivity ratio

All stuff will be fresh & genuine

USA FULL NAME SSN DOB DL ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL ACCOUNT & ROUTING NUMBER

UK FULL NAME NIN DOB DL ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL SORT CODE & ACCOUNT NUMBER

CANADA FULL NAME SIN DOB ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL MMN

#SSN #SSNDOBDL #SellSSN #CCShop #CCSELLCVV #ShopSSNDOBDLADDRESS #FULLZ #SSNFULLZ

#REALDLSCAN #YoungAgeFullz #Fullzseller #USAFULLZ #FULLZUSA #SellerSSNDOB #ShopSSNDOB

#SIN #SINDOBDL #SellSIN #SINMMNFULLZ #MMNPROSSIN #MMNSIN #CCShop #CCSELLCVV #ShopSINDOBDLADDRESS #FULLZ #SINFULLZ

#REALDLSCAN #YoungAgeFullz #Fullzseller #CANADAFULLZ #FULLZCANADA

#NIN #NINDOBDL #SellNIN #CCShop #CCSELLCVV #ShopNINDOBDLADDRESS #FULLZ #NINFULLZ

#REALDLSCAN #YoungAgeFullz #Fullzseller #UKFULLZ

Other stuff we’re providing as well, listed below:

===========

DL Front back with selfie USA|UK|CA|AUS|GR|FR|RU|CHINA e.t.c

Fullz with MVR & W-2 Form

Business Pros Company fullz with EIN

High credit scores pros (700+ score)

Dead fullz bulk quantity

Tax return filling fullz (FASFA|UBER|DOORDASH|SBA|PUA|UI|BENEFITS)

USA Fullz with DL Front Back with SSN & Selfie

Email Leads available in different categories:

===========

Crypto Leads

Fresh Sweep Stakes

Business P2P leads

Medical Leads

Education Leads

Country wise Leads

Bank Details Leads with phone numbers

Specific States & Cities Leads USA UK CAN

Car Database leads with registration No.

Doctor’s Leads

Health Leads

Facebook|Amazon|LinkedIn|Ebay Leads

Payday Leads

Mortgage Leads

All type of Sp’a’mming Tools & Tutorials are available for learning purpose.

>SMTP

>RDP

>BRUTES

>SHELLS

>C-panels

>Web-Mailers

>Bulk SMS & E-Mail Senders

>Sc@mpages & Scripting

>Cash out & Carding Tutorials

>H@cking Tools & Tutorials

Many other Stuff we can provide on demand as well

Feel free to contact with us, we’ll assist you 24/7

We’re providing stuff for learning to make money as well

Proper guidance & assistance will be provided

Waiting for you guy’s

Here we are for you:

-TG – @ leadsupplier / @ killhacks

-What’s App – (+1).. (727). (788). (6129).

-TG Channel – t.me/leadsproviderworldwide

-VK Messenger ID – @ leadsupplier