The Trip: Om Dar-Ba-Dar and the Birth of Indian Cinematic Anarchy

When Om Dar-Ba-Dar resurfaced in theatres in 2014 after twenty-six years in obscurity, it wasn’t rediscovered so much as decoded. Those who had hunted down bad VHS transfers and whispered about its strangeness finally had proof: this was the most unpredictable, anarchic film India had ever produced - once described as “the great Indian LSD trip.”

Made in 1988, Kamal Swaroop’s film unfolds in Ajmer–Pushkar, a world of fairs, frogs, and family rituals. The surface looks familiar - a boy named Om, his father who quits a government job to become an astrologer, a sister chasing her own desires - but the structure collapses quickly. The narrative disintegrates into myth, song, absurd comedy, and dream fragments.

Swaroop builds the film not from story but sensation. The opening sequence - trumpets blaring off-beat, colonial newsreel footage narrated by Om, a woman claiming to have been born through a cow’s organs sets the tone. From there, Om Dar-Ba-Dar becomes a delirious collage of history, advertisement, science, religion, and memory. It looks like a Bollywood musical but moves like a fever dream.

Swaroop, trained at the Film and Television Institute of India and influenced by Godard, Warhol, Buñuel, and his mentors Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani, constructs his madness with method. His collaborator, screenwriter Kuku, fills the film with non-sequiturs, puns, and bilingual jokes—like the recurring phrase “frog keychain,” which in Hindi sounds like frog ki chaeen, “the frog’s love.” The result is a surrealist film that uses form itself as commentary, both mocking and celebrating Indian pop culture.

Rajat Dholakia’s soundtrack extends this spirit of experimentation. His music borrows from radio jingles and film songs, looping them into satire until repetition becomes revelation.

When Om Dar-Ba-Dar returned through NFDC’s restoration, it found an audience ready to engage with its energy rather than decode its mystery. What once felt like chaos now looked prophetic. Its fractured rhythms anticipate a world shaped by mixed languages, rapid consumption, and endless reinvention.

When Om Dar-Ba-Dar premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1988, it confounded everyone who saw it.

A film that seemed to obey no rules, it drifted between myth and mockery, childhood and science, ritual and absurdity. Kamal Swaroop’s vision was unlike anything Indian cinema had attempted—restless, electric, and stitched together from fragments of memory, advertisement, and dream.

When Om Dar-Ba-Dar premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1988, it confounded everyone who saw it.

A film that seemed to obey no rules, it drifted between myth and mockery, childhood and science, ritual and absurdity. Kamal Swaroop’s vision was unlike anything Indian cinema had attempted—restless, electric, and stitched together from fragments of memory, advertisement, and dream.

For years, Om Dar-Ba-Dar survived as a ghost story — circulated through bootlegs and whispered about in film-school corridors.

Its official re-release in 2014 through NFDC and PVR revealed what the grainy copies had hidden: a delirious, meticulous experiment in sound and image. What once seemed chaotic now felt like prophecy — an India already fractured by information, noise, and imagination.

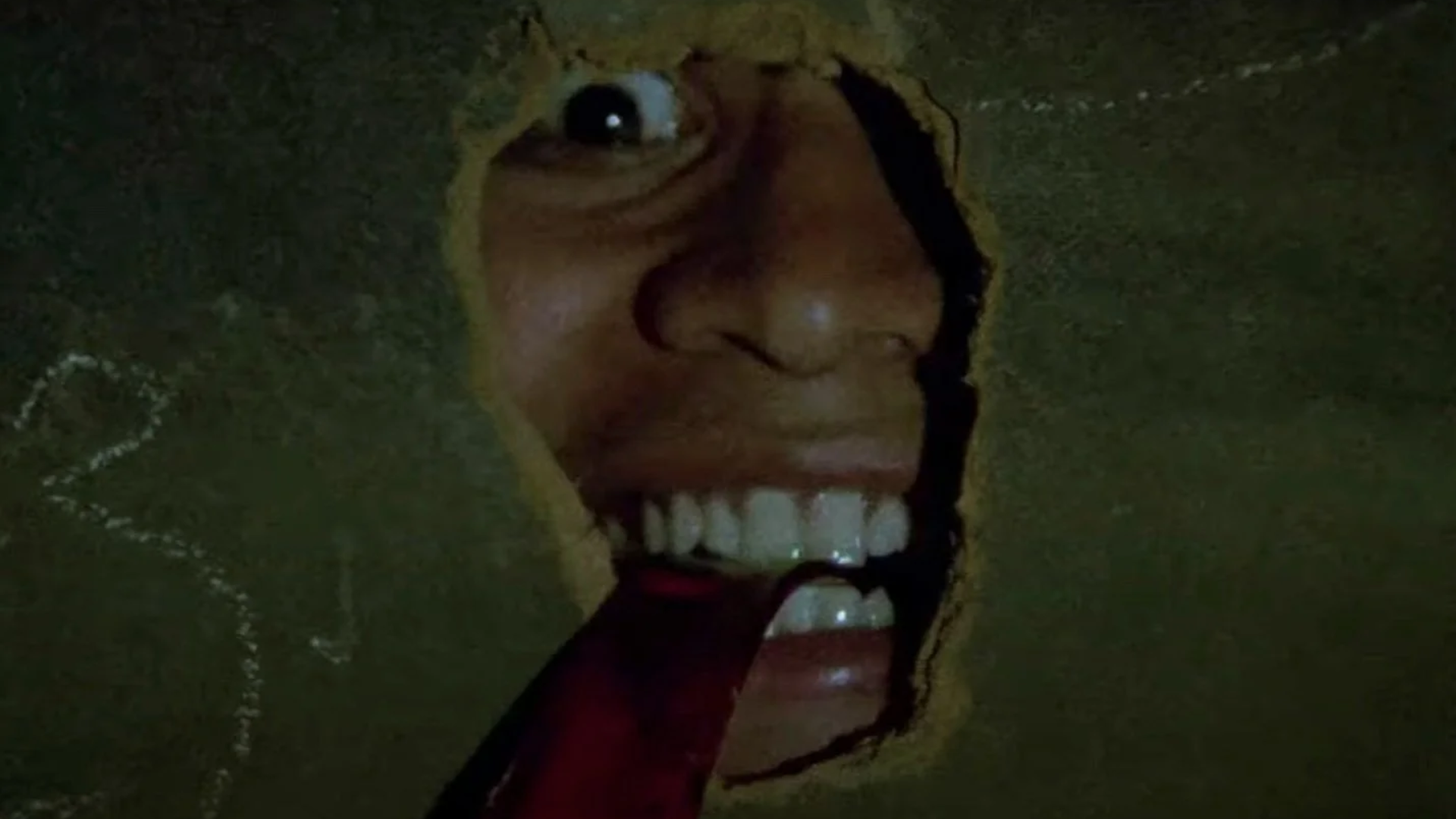

One of the film’s strangest and most memorable sequences involves frogs found with diamonds inside them, sparking a chaotic hunt across the town.

The image captures Om Dar-Ba-Dar’s absurd cosmology — where myth, greed, and biology collapse into the same delirium. It’s Swaroop’s surreal metaphor for India’s obsession with miracles, turning the ordinary frog into a vessel of divine absurdity.

Babli Teliphon Se

Babli Teliphon Se plays like a pop parody that accidentally becomes cosmic. It borrows from the language of Hindi film songs and radio jingles, only to twist them into absurdity. Beneath its humour is a sharp critique of how technology, romance, and media began to blur in the Indian imagination long before the internet made it real.

Tadpole Se Hum

Tadpole Se Hum is the film’s strange philosophy lesson disguised as a nursery rhyme. It captures the absurdity of evolution and identity in Swaroop’s universe — where the leap from tadpole to human is both literal and cosmic. The song drifts between joke and prophecy, echoing the film’s central idea: that progress in India often feels like metamorphosis without direction.

Meri Jaan A... Meri Jaan B

Meri Jaan is the film’s beating heart — a delirious fusion of love song, political slogan, and street performance. It mocks the sentimental structure of Bollywood music while becoming something hypnotic on its own terms. Rajat Dholakia’s score turns repetition into rhythm, chaos into choreography — an anthem for a film that refuses to make sense quietly.

Anurag Kashyap on Om Dar-Ba-Dar

Anurag Kashyap has often credited Om Dar-Ba-Dar as a personal awakening. Its irreverence and chaos gave him license to be fearless with form. In his blog, he noted that “Emotional Attyachar” from Dev.D was directly inspired by the film’s song Meri Jaan — not just musically but in spirit. It was Swaroop’s madness, Kashyap said, that “freed” Indian cinema.

Imtiaz Ali on Om Dar-Ba-Dar

For Imtiaz Ali, Om Dar-Ba-Dar remains the film that made Indian indie cinema possible. He called it “old wine” — aged, potent, and misunderstood for decades. Ali spoke of how its belated release only amplified its myth: a reminder that true originality doesn’t age. Its influence, he said, still lingers in every filmmaker who dares to follow instinct over structure.

Kiran Rao on Om Dar-Ba-Dar

Kiran Rao first watched Om Dar-Ba-Dar on a VCD riddled with missing frames and distorted sound. Yet even in fragments, she could sense its brilliance. The gaps, she said, forced her imagination to complete the film — turning imperfection into part of the experience. Few films can survive decay like that; fewer still become more powerful through it.

Kamal Swaroop on Parallel Cinema

Comments

MRS DEJANA IVICA — 1 day ago

TANGIBLE INFORMATION ABOUT LOAN PLANNING… THIS HAPPY NEW YEAR..

This is not a normal post that you see every day on the internet where people give fake reviews and false information about excellent financial assistance. I am aware that many of you have been scammed and that fake agents have taken advantage of those seeking loans. I will not call these normal reviews, I will call this situation where I live a witness to how you can get your loan when you meet the company’s requirements. It really does not matter if you have a good credit rating or government approval, all you need is a proper ID card and a valid IBAN number to be able to apply for a loan with an interest rate of 3%. The minimum amount is 1000 euros and the maximum amount that can be borrowed is 100,000,000 euros. I give you a 100% guarantee that you can get your loan through this reliable and honest company, we operate 24 hours online and provide loans to all citizens of Europe and outside Europe. They sent me a document that was checked and tested before I got the loan, so I invite anyone who needs a loan to visit them or contact them via email: michaelgardloanoffice@gmail.com

WhatsApp for Europe: +38591560870

WhatsApp for USA: +1 (717) 826-3251

After you contact them, let them know that Mrs. Dejana Ivica from Zagreb gave you the information. Seeing is believing and you will thank me later when you get a loan from them. I made a promise that after I get a loan from them, I will post the good news to everyone online. If you have friends or relatives, including colleagues, you can tell them about this offer and that it is happening.

Christopher William —

DR UYI has done it for me, His predictions are 100% correct, He is real and can perform miracles with his spell. I am overwhelmed because I just won 336,000, 000 million Euro from a lottery jackpot game with the lottery number DR UYI gave me. I contacted DR UYI for help to win a lottery via Facebook Page DR UYI, he told me that a spell was required to be casted so that he can predict my winning, I provided his requirements for casting the spell and after casting the spell he gave the lottery numbers, I played and won 336,000,00 euros. How can I thank this man enough? His spell is real and like a God on Earth. Thank you for changing my life with your lottery winning numbers. Do you need help to win a lottery too? contact Dr UYI via drzukalottospelltemple@gmail.com OR WhatsApp on +17174154115

Tracy —

HIRING GENUINE HACKERS TO CONSULT RECOVERY SPECIALISTS

I want to sincerely thank Safeguard Recovery Expert for their extraordinary skill; they are real heroes, and I wish I had met them sooner rather than reaching out to other hackers for help. If you read this comment, you might be able to get your hacked or blocked bitcoin investment back. I’m posting it for anybody who have been affected by cryptocurrency investment, mining, and trading frauds.

Email:

safeguardbitcoin@consultant.com

Website: safeguardbitcoin.wixsite.com/safeguard-bitcoin—1

WhatsApp:

+39 (350)-976-(4936) //// +49 (1573) – (355)-(9226)

Big Bull —

SELLING FULLZ SSN USA NIN UK SIN CANADA

AUS SPAIN ITALY GERMANY Fullz available

Fresh Stuff & Fresh Spammed

Available in bulk quantity

Valid & guaranteed info

DL front back with selfie

DL with issue & exp dates

DL with SSN

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS—> USA

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS—> UK

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN—> CANADA

Tax Return Filling Fullz & KYC Stuff

HACKING & SPAMMING TOOLS & TUTORIALS

COMPLETE PACKAGES WITH ALL TOOLS & TUTORIALS INCLUDED

SCAM PAGES|SCRIPTING

CASH OUT & CARDING STUFF

LOAN METHODS & CARDING METHODS

Many Other stuff for cashing out|filling for loans|KYC

All stuff will be 101% Genuine, nothing generated or edited

Contact us here only (Be aware from scammers)

Telegram – @ killhacks ’ @ leadsupplier

What’s App – +1 7277..88..612..9

TG Channel – t.me/ leadsproviderworldwide

Email – hacksp007 at gmail dot com

VK Messenger – @ leadsupplier

USA STUFF:

SSN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS EMPLOYMENT & BANK INFO FULLZ

SSN DOB DL ADDRESS DL ISSUE & EXP INFO FULLZ

FULLZ WITH MVR

USA DL|ID FRONT BACK WITH SELFIE & SSN

USA LLC DOCS

USA W-2 FORMS

USA Passport Photos

High Credit Scores Pros

SweepStakes & Dead Fullz

Business EIN Company Pros|EIN Lookup

Dumps & CC with CVV

-———————————————————————-

UK (UNITED KINGDOM) STUFF:

NIN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS FULLZ

NIN DOB DL ADDRESS SORT CODE & ACCOUNT NUMBER FULLZ

High Credit Scores Pros Fullz

UK DL Front Back with Selfie

UK Email & Phone number Leads

UK Passports

Consumer Leads UK

Bank Leads with sort code & account number UK Fullz

-———————————————————————-

CA (CANADA) STUFF:

SIN DOB ADDRESS FULLZ

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN FULLZ

SIN DOB ADDRESS MMN PHONE POST CODE FULLZ

Canada DL Front Back with Selfie

CA Email & Phone Number leads

High Credit Score Fullz

Canada Passports

-————————————————————————

OTHER STUFF WE’RE PROVIDING WITH GUARANTEE:

EMAIL LEADS (Crypto|Unemployment|Casino|Medical|Health|Office365)

Car Database with Vehicle registration numbers

Email Combos

I.P & Proxies

Different type of Docs available

TOOLS AVAILABLE

SMTP RDP SHELLS C-PANELS

KALI LINUX

RATS & VIRUSES

Web-Mailers

SMS & Email Senders

Scam Pages & Scripting

Office365 Spamming Stuff

#FULLZ #TOOLS #TUTORIALS #EBOOKS #USAFULLZ #UKFULLZ #CAFULLZ #DLPHOTOS

#HACKING #SPAMMING #CARDING #SPOOFING #LEADSUSA #COMBOS #CRYPTOLEADS

#UKLEAD #CANADALEADS #HIGHCREDITSCOREPROS #CRYPTOPAYMENTS #PROS #OFFICE365

#SENDERS #FULLZSHOP #DUMPSCVV #CCFULLZ #USACC #FULLZDUMPS #DUMPSID #DUMPSDL

#EMAILLEADS

Contact here only (Be aware from scammers)

Telegram – @ killhacks ’ @ leadsupplier

What’s App – +1 7277..88..612..9

TG Channel – t.me/ leadsproviderworldwide

Email – hacksp007 at gmail dot com

VK Messenger – @ leadsupplier

Johnson Elizabeth —

Best Crypto Recovery Company – visit Optimistic Hacker Gaius.

Optimistic Hacker Gaius is the best crypto recovery company. I was scammed and lost a significant amount of funds, but after reading a review about their success in recovering lost crypto, I reached out. Within just 6 hours, they traced and recovered most of my lost assets! Their service was fast, professional, and exceeded my expectations. I’m extremely grateful for their help and highly recommend them to anyone facing similar issues. Thank you, Optimistic Hacker Gaius!

Contact them at the following.

Visit Their Website: optimistichackargaius. c o m

Email: support@ optimistichackargaius. c o m

Text them on WhatsApp: (+44 737 674 0569).

rocio cardenar —

Investment scams are becoming increasingly common in the world of cryptocurrency, with many individuals falling victim to fraudulent schemes promising high returns on their investments. These scams can result in the loss of significant amounts of money, leaving victims feeling helpless and devastated.

CoinsRecoveryWorldwide is a trusted and reliable resource for individuals who have fallen victim to investment scams involving Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. They specialize in helping clients recover their lost assets and funds through their expertise and experience in navigating the complex world of cryptocurrency scams.

CoinsRecoveryWorldwide works tirelessly to investigate and track down the perpetrators of these scams, working with law enforcement agencies and other authorities to ensure that justice is served. They provide a range of services to assist clients in recovering their assets, including legal representation, forensic analysis, and negotiation with scammers.

If you have been the victim of an investment scam involving Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies, don’t hesitate to reach out to CoinsRecoveryWorldwide for assistance. They have a proven track record of success in recovering lost assets for their clients and can help you navigate the process of recovering your funds. Don’t let scammers get away with your hard-earned money – contact CoinsRecoveryWorldwide today for help in recovering your assets.

Contact information

WEBSITE; https://coinsrecoveryworldwide.mobirisesite.com/ EMAIL.COINSRECOVERYWORLDWIDE@GMAIL.COM WHATSAPP:+17658236083]

MRS DEJANA IVICA —

TANGIBLE INFORMATION ABOUT CHRISTMAS LOAN FOR PLANNING…

This is not a normal post that you see every day on the internet where people make false statements and false information about huge financial assistance.. I am aware that many of you have been scammed and that fake agents have taken advantage of those seeking loans. I will not call this a normal statement, I will call this situation where I live a witness to how you can get your loan when you meet the company’s requirements. It really does not matter to have a good credit rating or government approval, all you need is a valid ID card and a valid IBAN number to be able to apply for a loan with an interest rate of 3%. The minimum amount is 1000 euros and the maximum amount that can be borrowed is 100,000,000 euros. I give you a 100% guarantee that you can get your loan through this reliable and honest company, we operate 24 hours online and provide loans to all citizens of Europe and outside Europe. They sent me a document that was checked and tested as valid before I got the loan, so I invite anyone who needs a loan to visit them or contact them via

Email: michaelgardloanoffice@gmail.com

WhatsApp for Europe: +385915608706

WhatsApp for USA: +1 (717) 826-3251

After you contact them, let them know that Ms. Dejana Ivica from Zagreb gave you the information. Seeing is believing and you will thank me later when you get a loan from them. I made a promise that after I get a loan from them, I will post the good news to everyone online. If you have friends or relatives, including colleagues, you can tell them about this offer and that it is happening this CHRISTMAS. ’’’’’’’

Fat Rosa —

HOW I RECOVERED MY LOST CRYPTO FROM FAKE BROKER ONLINE.

I had lost over $752,000 by someone I met online on a fake investment project. After the loss, I had a long research on how to recover the lost funds. I came across a lot of Testimonies about THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS. I contacted them providing the necessary information and it took the experts about 48 hours to locate and help recover my stolen money. If anyone is looking for a Recovery firm to Recover your lost Crypto. You can contact THE HACKANGEL RECOVERY TEAMS . I hope this helps as many out there who are victims and have lost to these fake online investment scammers. You can contact them by using

Email at support@thehackangels.com

Website at www.thehackangels.com

WhatsApp +1(520)200-2320